| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVI Number 20. . . .January 29, 2010

excerpt:

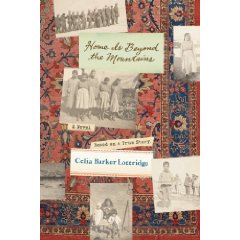

Samira's fear is justified. She is a member of an Assyrian family living in Persia near the Turkish border in 1918. Turkey, an ally of Kaiser Wilhelm's Germany, is about to invade. Up until the peace settlement following World War I, Turkey (the Ottoman Empire) controlled much of the near east, including the area that is now Iraq. Persia (now Iran) was neutral, but Turkey had territorial ambitions and did not respect its neutrality. In the spring of 1918, 80,000 Assyrians and many Armenians living in Persia near the Turkish border fled for protection from their villages to the British army lines, several hundred miles away, for protection. Half these refugees died en route. Although the Armistice ending the Great War was signed on November 11, 1918, the peace settlement, which involved dismantling the Ottoman Empire, took several years. Meanwhile, the Assyrian refugees, including orphan children, were held in camps run by the British. One of the largest was north of Baghdad. In Home is Beyond the Mountains, author Celia Barker Lottridge shares a family story. Her mother, Louise Shedd, the daughter of an Assyrian mother and an American missionary father, was sent in 1915 from Persia to relatives in California because of the Assyrians' precarious situation. The real Louise escaped the fictional Samira's experiences. In 1922, Louise's elder sister (the author's aunt), Susan Shedd went back to Persia to direct an orphanage for refugee children in Hamadan. Her letters and stories were the author's main source, along with newspaper articles and letters from other Americans who visited the refugee camps. In the first part of the novel, the author presents a warm, colourful picture of village life. Samira grew up in a one-room whitewashed house with beautiful carpets, an oven in the floor and the family's winter food stored in a root cellar. Boys attended a school run by the Assyrian Orthodox Church, but, although the priest promised a girls' school, no teacher arrived for them. Lottridge vividly depicts the gruelling march to safety which takes the lives of Samira's parents and younger sister, but not her brother Benyamin. In the camps, Samira makes friends with a variety of children, each embodying a different refugee experience. Samira and the other teenage girls mother the younger orphans, learn to read and to operate sewing machines, and generally strive to make the camps as homelike as possible, yet even creative ways of dealing with hardship become repetitive. Halfway through the novel, reading the sentence, "Life in the Hamadan Orphanage went on as if the children would be there forever," I found myself agreeing. A few pages later, however, Susan Shedd announces her plans to lead around 300 children on a march back to their home villages, and the story picks up. Miss Shedd stands out as a charismatic, colourful figure. "She's not like the other ladies," Samira tells her friend Anna. "She speaks Syriac almost the way we do." In October, 1923, about to lead the trek, she "was wearing trousers and a jacket, and she carried a small whip under her arm. 'Why does she have that whip?' asked Anna. Benyamin answered, 'A horse sometimes needs a touch of the whip. Anyway, she's riding like a man, not a fine lady, so she has to have what a man would have.' Samira thought he was right. Miss Shedd could not look like a weak woman. Not on this journey." The fictional Samira, like the real Susan Shedd, is a credit to her gender. As the novel progresses, she enhances her survival skills and becomes literate and numerate. Benyamin "wants to do more in the world than tend vines and take care of sheep," and so, instead of returning to their village, he stays in Tabriz for further education. Because the story does not follow Samira into adulthood, readers never find out how her hard-won knowledge impacts upon her life as a woman. Through her characters, Lottridge pays tribute to the spirit and endurance of the real children who survived the march. In recent years, the West has been reminded of the events of 1915 which are known to Armenians as the "Great Calamity." Now, Lottridge has made us aware of the sufferings of another unique cultural group, the Assyrians. Grownups who read Lottridge's novel may want to further their historical knowledge of the near East through an internet search and by reading Margaret MacMillan's Paris 1919. Recommended. Ruth Latta's latest book is a novel for grown-ups, Spelling Bee (Ottawa, Baico, 2009). Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- January 29, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |