| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XVI Number 20. . . .January 29, 2010

excerpt:

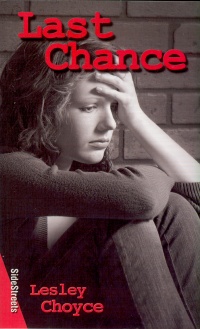

Sixteen-year-old Melanie is living on the streets of Halifax when she meets Trent, also homeless. Because they are both trying to stay in school and Trent knows how tricky that can be if you are homeless he invites Melanie to crash at his apartment. Together, they struggle at menial jobs, working 10 p.m. until 2 a.m. at Donut World, and desperately try to stay awake at school during the day. When their paychecks are delayed for a week, a cash emergency ensues for the rent is already overdue and eviction is just around the corner. The pair considers various options out of their difficulties: dropping out of school, going into a group home, and Melanie becoming pregnant. Eventually the moody Trent tells Melanie he has landed a night job loading boxes. In reality, he has dropped out of school to become a male prostitute. Choyce’s stark novel, previously published as Falling Through the Cracks in 1996, offers a frank, although not necessarily hopeless, portrayal of life for teenaged runaways. Unfortunately, the plot consists of an ever-escalating string of trials and tribulations, and there is little character development. Melanie, for example, seems much too adult for her years. Choyce makes it clear that she was right in leaving her verbally abusive parents, but it seems unrealistic for her to be so much wiser than every adult around her. Her only “growth” as a character comes at the end when she learns how to manipulate the social service system in order to get money so that she and Trent can continue living on their own. Trent, too, is a problematic character. He is variously described as smart, protective, moody, prone to bursts of anger, and finally, out of the blue, homosexual. It begins to feel as if Choyce had a checklist of issues that he wanted to include in his description of runaway kids. Given that so many teens go through periods of strained parental relationships when they contemplate leaving home, this is a book that has a kind of didactic appeal. Unfortunately, Choyce offers no examples of teens and parents even attempting to work through their difficulties, only a catalog of what can go wrong on the streets and one example of a system loophole. Recommended with reservations. Kay Weisman is a Master of Arts in Children’s Literature candidate at the University of British Columbia. Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE

- January 29, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |