| ________________

CM . . . . Volume XVI Number 29. . . .April 2, 2010.

|

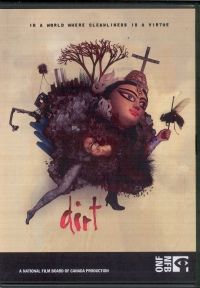

Dirt.

Meghna Haldar (Writer & Director). Tracey Friesen (Producer). Rina Fraticelli (Executive Producer).

Montreal, PQ: National Film Board of Canada, 2007.

81 min., 39 sec., DVD, $99.95.

Order Number: 153C 9107 404.

Grades 12 and up / Ages 17 and up.

Review by Frank Loreto.

***/4

|

| |

|

Many years ago, on the way to my piano lesson, I found a foil disk on the road. Thinking it was a candy or chocolate coin, I scooped it up and was disappointed to find it was neither. However, as it looked like some kind of balloon, I was eager to pull it out and see. Unfortunately, since I was late for my lesson, I put it in my pocket for later. My habit was to try to distract my piano teacher with conversation as I rarely was prepared for my lesson. “Look Sister,” I said, “I found a balloon.” When she saw what I had, she threw it into the garbage and said that it was dirty. “No,” I assured her, “It was wrapped up in foil.” I could not understand why she would not give it back to me. However, her claim that it was dirty stuck in my mind. I do not know exactly how many years later I fully understood what I had brought out of my pocket. I almost miss that innocence.

In Dirt, filmmaker, Meghna Haldar examines the concept of what makes something or someone dirty. Early in the film, she states that after 9/11, living in the United States, she felt that people were looking at her darker skin with suspicion and she felt in some way, dirty. This pushed her to probe our fascination with and repulsion of dirt and to ask, “What is it about feeling dirty that shames us?” She states, “Questions about dirtiness consumed me. I want answers. I want to talk about dirt.”

And talk she does as she takes the viewer on a wide and detailed treatment of this topic. She comments that “the gods created man out of spit and dirt and yet we have an aversion to all things dirty.” Haldar presents an artist who creates images of the gods using mud gathered by the Ganges River. The mud is filled with filth, and the artist admits that he often gets rashes working in this medium. Next we are taken to New Mexico to the Church of Dirt. People flock to this church as the dirt around it seems to have miraculous curing powers. The priest admits that he carts the dirt in from another place, but the faithful have no problem with that. A woman interviewed says that she is taking some dirt back to her mother who has cancer. She does not know if it will work, but she is willing to try.

Haldar states that “dirt” comes from “drit,” the Old English word for excrement. She points out that we “share a disgust for shit——especially other people’s shit” and yet excrement on a field acts as fertilizer for the crop which we eventually eat. Waste products are processed and sold back to those who produced it.

She shows that “a pile of poop is a living universe.” From a biological point of view, this aspect of the film is fascinating. What most people take for granted as disgusting is a vibrant, essential part of the life web.

On the topic of excrement, Haldar takes viewers to India and introduces a couple who haul away human waste. She points out that the poor are seen as dirty while the respectable are seen as clean. The poor districts are seen as “disease centres.” The wife who has married beneath her caste admits that, if her husband appeared at her parents’ house, “they would wash the entire house with water from the Ganges.” She tells her parents that she has a job serving tea in an office. If they were to know the truth, they would never let her touch the dishes in their house. So, while they help keep the city clean, they are seen as unclean and to be shunned.

Haldar shows the impact of European standards of hygiene on the colonial areas. Advertisements for Pears soap claimed it able to “wash coloured skin white.” Residential schools cut the students’ hair and had them de-loused in an attempt “to wash the Indian out of the Indian.” She shows how Hitler presented the Jews as dirty and, for the good of the country, said they should be removed or cleansed. The use of dirt as a rationale for ethnic cleansing is a historical fact. At this point, some very graphic concentration camp film footage is featured.

The film moves on to the area of sex-trade workers. The woman featured admits that no one wants a sex-trade worker living next door. When her parents learned of her line of work, they were convinced they had done something to her “to make her do something so terrible.” The connection between sex and dirt goes back to my “balloon” discovery.

Dirt is a thought-provoking discussion about something we would just as soon not dwell on. For example, Haldar points out that we need garbage workers to take away our trash and then we look down our noses at them for doing so. Contradictions abound, and she does a fine job showing them. She has taken a very wide brush in painting her topic. Unfortunately, there is too much in this film for one treatment. In fact, there is potential here for a series of films based on each of her areas of discussion.

As interesting as the topic is, this is not something that would work in a classroom. As the topic insists, the language is graphic and crude. At times, the images are shocking and not appropriate for a school audience. For an adult audience. however, there is much to think about here.

Recommended with reservations.

Frank Loreto is a teacher-librarian at St. Thomas Aquinas Secondary School in Brampton, ON.

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to

cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

NEXT REVIEW |

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS ISSUE- April 2, 2010.

AUTHORS |

TITLES |

MEDIA REVIEWS |

PROFILES |

BACK ISSUES |

SEARCH |

CMARCHIVE |

HOME |