| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXI Number 35. . . .May 15, 2015

excerpt:

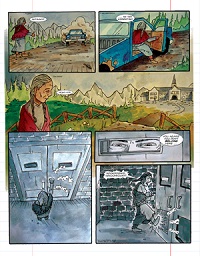

This book clearly is made in response to timely political concerns in Canada’s history. It links past injustices imposed by the Canadian government to current injustices experienced by Canada’s Indigenous people. The content is presented as an accessible and creative approach to graphic novels. The actual graphic novel portion of the book is broken up into five chapters, with the Uncut Version having a sixth chapter. The first chapter begins with a quote by Prime Minister Stephen Harper “We (Canada) … have no history of colonialism….” The chapter juxtaposes this statement with the graphic depictions of the forced removal of First Nations children from their home and families and their brutal treatment at the Residential Schools. Children were placed into these schools, their clothes were taken from them and replaced with numbered uniforms, and siblings were separated. The second and third chapters expose the aggressive assimilation policies supported by law, where the law, essentially forced parents to sign away legal rights to their children. Parents were not allowed visitation rights and were forced to sign papers giving the school principal complete guardianship of the children while at the residential schools. The fourth chapter articulates the damage residential schools had on the loss of culture. Young children who knew no English would be beaten and abused if they uttered any words in their indigenous language. In the fifth chapter, relief seems to finally arrive with the closure of residential schools in 1996; however, this action was not without resistance by ‘respected’ members of the ‘education’ community. The sixth chapter, included in the Uncut Version only, depicts the cycle of sexual abuse that resulted from the residential school experience, and it clearly depicts the sexual abuse inflicted on First Nations children by the adults at the residential schools. It also explains the sexual abuse between students at the school. With the degree of hurt, pain, and confusion experienced in First Nations’ children in their formative years, the chapter flashes forward to look at the negative spiral effects on these children as adults, including cycles of inflicted sexual abuse, cultural abuse, and violence. Finally, there is a sneak preview of the second volume of the series. Even though the residential schools have been closed, this is not the end of their effect on modern society. The part two sneak peak explores some of the negative repercussions experienced by residential school survivors and their families. This book’s design has been given a lot of consideration. It is printed to look like a school subject note book, with blue lines stretching across each page. The preface, which includes newspaper clippings, photographs, and quotes, appears to be photocopied or cut and pasted into the note book with selective commentary in the margins. The selected clippings are grouped and sorted by topics exposing the widespread abuse that occurred at residential schools. Additional clippings of a more gritty nature are included in the Uncut Version. The graphic novel portion is artistically depicted. It shows life at residential schools in sepia or black and white, and life outside the residential schools in colour. The images are framed within the context of note pages that contribute to the story. The art is very effective in making the residential school teachers appear intimidating and downright deadly. The graphic novel art appears to be pasted on top of the school paper. The images that appear in the Uncut Version’s sixth chapter highlight the negative cycle of abuse and appear tattered, burned, and taped back together in the note book. The process of tattering and taping the photos aid in disguising the full graphical impact of abuse but remain equally effective in sharing this history. The tatters of the photos also metaphorically represent the residential schools’ attempt to ignore this abuse. Eaglespeaker’s UNeducation Volume 1: A Residential School Graphic Novel is a moving work that helps open the conversation about the atrocities that took place in Canada’s residential schools. While the book does not censor the realities experienced at residential schools, it does tastefully select scenes to represent these realities so as to not completely overwhelm audiences. I would recommend this particular graphic novel as part of any school study involving First Nations studies or the history of Canada. While available for independent reading, it seems a highly valuable piece in generating group discussion and reflection. Recommended.

Rachel Yaroshuk is a Teen Services Librarian at Burnaby Public Library in Burnaby, BC..

To comment on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

CM Home |

Next Review |

(Table of Contents for This Issue - May 15, 2015.)

| Back Issues | Search | CM Archive

| Profiles Archive |

This graphic novel is unique in its composition. It comes in two versions, a PG Version and an Uncut version. The two versions are essentially identical, but the Uncut version has additional details that are more gritty, including a chapter titled “The Cycle”.

This graphic novel is unique in its composition. It comes in two versions, a PG Version and an Uncut version. The two versions are essentially identical, but the Uncut version has additional details that are more gritty, including a chapter titled “The Cycle”. This book, in both versions, includes a formal “Foreword” and a “Preface” that help situate this work in relation to large political movements. In June 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a public apology to all Indigenous people who were victims of the Canadian Residential School system. This symbolic act preceded Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) where hope was offered for family and survivors of Residential Schools, helping expose the truth about this period of Indigenous history. Six years later, Indigenous people are still denied access to historical documents that will expose the truth and inspire healing and closure to this tragic page in Indigenous history.

This book, in both versions, includes a formal “Foreword” and a “Preface” that help situate this work in relation to large political movements. In June 2008, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a public apology to all Indigenous people who were victims of the Canadian Residential School system. This symbolic act preceded Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) where hope was offered for family and survivors of Residential Schools, helping expose the truth about this period of Indigenous history. Six years later, Indigenous people are still denied access to historical documents that will expose the truth and inspire healing and closure to this tragic page in Indigenous history.

In the “Foreword”, adastracomix.com founder Nicole Marie Guiniling notes:

In the “Foreword”, adastracomix.com founder Nicole Marie Guiniling notes:  In the “Preface”, author Jason Eaglespeaker states:

In the “Preface”, author Jason Eaglespeaker states: