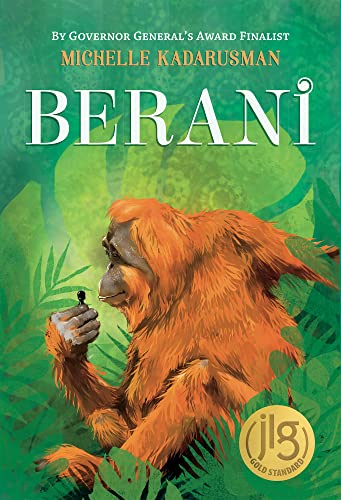

Berani

- context: Array

- icon:

- icon_position: before

- theme_hook_original: google_books_biblio

Berani

“This is a complicated subject, Malia. It is not as simple as it appears,” Mrs Harwono says once class is over. “I know your intentions are good, but I cannot allow a petition to go home with the students without permission from the principal. Especially as the school name is included.”

“But it’s not fair what is happening to the forests and the orangutans. Why can’t we protest? What does it have to do with the school?”

“You must understand that what the students do reflects on our school. Many parents in our community are involved in agriculture and various levels of government. What you are doing might inflame some of these people. I am not saying you do not have a right to protest. You do. But circulating a petition that involves the school – this must first be approved by the principal.”

“But he won’t approve it, will he?”

“Probably not,” she admits. “But I will try. I promise I will try”

She pats my hand. “I want you to know that I admire your convictions. I truly do. But there are rules we must follow here. This is not Canada.”

Her comment stings. “I know where we are,” I say, unable to keep the anger from my voice. “I am Indonesian.”

Malia, a budding activist, decides to use a class project to bring the plight of the orangutans in Indonesia to her classmates. When her mother expresses her concern, Malia promises she will discuss the project with her teacher before the presentation, something which she fails to do. Then, when her teacher refuses to allow her to hand out paper petitions until she receives permission from the principal, Malia decides to post the petition online because, after all, her teacher didn’t say she couldn’t. The consequences of her actions impact more than just herself. Her teacher, Mrs. Harwono, is put on leave, her best friend is called into the principal’s office, the school is pressured to teach the children the “right” information about palm oil, and Malia is suspended. The school offers her an ultimatum: sign a written apology which includes a statement indicating she now understands she was wrong, or she and Mrs. Harwono may not be returning to school.

The reader follows Malia as she struggles with her choices. Her feelings are further complicated by her family’s situation. Malia comes from a place of privilege with wealth, and her mother has Canadian citizenship. In fact, her mother plans to move to Canada soon. Malia knows she is wholly Indonesian, but her lighter skin and Canadian mother mean she is also half-Canadian. Throughout the novel, Malia begins to understand that her privilege means that the consequences of her actions impact her differently than the collateral damage that is impacting those around her.

In alternating chapters, the reader is also introduced to Ari, a student whose living situation is very different from Malia’s. His extended family scraped together enough money for him to attend a public school in the city where he now lives with his uncle. To help pay for this opportunity, he works in his uncle’s restaurant. He knows how fortunate he is, but he is also filled with guilt because he was chosen for this opportunity instead of his cousin who is a girl. Although she was a diligent and gifted student with the same dreams of education as Ari, she had to stay in the village and work in the rice fields. When Ari is handed Malia’s petition during a visit to her private school for a chess tournament, he realizes his uncle’s pet orangutan, Ginger Juice, is being kept illegally. He struggles with what he can do for her. Is there anything he can do to improve the orangutan’s living situation? Should he report his uncle to the authorities? He worries about his uncle’s anger and other possible consequences if he decides to act – or chooses not to.

The other character to tell her tale is Ginger Juice, the orangutan owned by Ari’s uncle. Ginger Juice lives in a cage and has become an attraction for the restaurant. Her chapters describe her before-life with her mother in the jungle (where she was known to the other orangutans as Berani) and how she ended up in her cage as well as her current situation. The uncle started putting her in the cage when she was younger and she misbehaved, and then he permanently moved her into the cage as she grew larger. Now, as an adult, she has grown too big for the cage and wouldn’t fit through the door even if it was opened.

Author Michelle Kadarusman deftly weaves several social justice messages through the narratives of her three protagonists while giving readers a glimpse into the standard of living for different families in Indonesia. The main narrative, of course, revolves around the loss of orangutan habitat due to the destruction of the jungle to grow palm trees. At the end of the novel, Kadarusman includes notes to further educate her readers about orangutans and how they can be helped. Also included in the notes is a glossary that provides definitions for some of the Indonesian words found in the novel. The additional issues and storylines add richness to the narrative that brings Kadarusman’s story alive within its appropriate cultural and societal context.

I particularly appreciated how the author depicted the wide-ranging consequences of choices and activism. The author carefully suggests to readers some of the possible impacts Malia’s and Ari’s choices may have on their futures as well as on the lives of others. She also explores the idea of privilege and sheds a light on the different standards of living that exist within society.

Kadarusman’s novel exudes the positive message that everyone can make a difference while also reminding readers that there are always consequences – good or bad - to the choices one makes and that many situations are not as black and white as we perceive. The “and they lived happily ever after” plot lines of each of the protagonists may not be entirely realistic, but ending the novel with hope felt right.

Jonine Bergen is a teacher-librarian in Winnipeg, Manitoba.