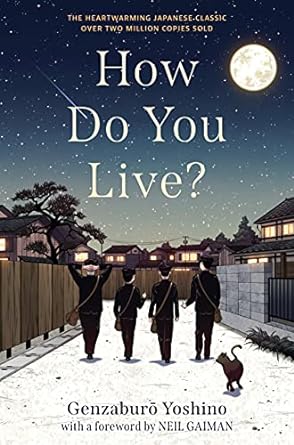

How Do You Live?

How Do You Live?

Touted as a “heartwarming Japanese classic with over two million copies sold”, this 2021 translation – bestowing a 1937 Japanese schoolbook upon English speakers for the first time – is feted with a foreword by Neil Gaiman. Sounds like a winner. But alas, it’s lost in time and translation.

Let’s start with the author. Born in 1899, he earned a degree in philosophy, was an advocate for peace, and, after being arrested and eventually released by pre-war Japanese “Thought Police,” was assigned to write an ethics textbook for young people. Instead, he wrote a story about a boy growing up in 1930s Japan – a book that “contains many lessons and a quiet but powerful message on the value of thinking for oneself and standing up for others during troubled times.”

Basically, each time 15-year-old protagonist Copper (nicknamed after Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus) has an experience or adventure (bullying, or witnessing poverty or listening in on a discussion of Napoleon), his uncle pontificates to him about it in a journal – belaboring a philosophical point or history lesson for pages upon pages.

The book is mostly in Copper’s point of view, interspersed with his uncle’s journal writings.

Today’s pre-teens and teens, besides being more or less allergic to in-your-face lectures, will in no way relate to Copper’s language or adventures, let alone his uncle’s drawn-out soapbox harangues and contemplation. Nor does Copper feel like a 15-year-old in this book:

“This Sunday, do you want to come play at my house?”

The two of them stood there, arms around each other, and sobbed.

It would be great if this were a compelling read to which contemporary pre-teens could relate, one that inspires them to contemplate ethics. But the language alone is a world away from contemporary dialogue. Here’s how a teacher handles a playground fight in the book, addressing

the culprits:

“Please be honest. In starting a fight and creating this commotion, you are thoroughly in the wrong. But you are still young. Your character is still in formation. If you were unable to restrain your anger, you needn’t necessarily be condemned for that. If one were to feel that this act was not entirely without cause or reason, one might in that case expect to see more restraint from you in the future.”

Picture a teacher using those words on school grounds today. Okay, I saw your raised eyebrow, heard your guffaw. Now picture a current pre-teen reading that section of this book. He or she would surely toss the book across the room and search for something more current, unless amused by someone’s version of how teachers may have spoken to errant students in Japan 100 years ago.

More time-warp quirkiness (or signs of an over-philosophic author):

“Copper had an odd feeling. The watching self, the self being watched, and furthermore the self becoming conscious of all this, the self observing itself by itself, from afar, all those various selves overlapped in his heart, and suddenly he began to feel dizzy.”

The book tries; it really tries. The writing is often strong:

Kurokawa’s face was thick skinned and pimply like the rind of a bitter orange, and with his big grin he seemed at times to be laughing at Copper.

And to be fair, the platitudes, whether or not they land and stick on today’s readers, are well-meant and potentially thought-provoking.

“You must not lose the spirit that woke you in the middle of the night, to follow your own questions wherever they lead!”

“The human tendency to think about things and form judgments with ourselves at the center remains deep-rooted.”

“If someone has a noble mind and great insight, then we owe it to them to respect them as great, even if they are impoverished.”

“In the pain of our mistakes there is also human greatness.”

Ironically, sometimes the book’s appeal is the time gap and foreign setting. Some readers will be intrigued by how things were back in 1930s Japan:

If Uragawa got up from his seat for a minute during penmanship class, he’d return to find that his writing brush had disappeared.

It was a humble north-facing room the size of three tatami mats… They warmed their

hands from both sides of a Seto hibachi, a ceramic fire bowl.

Unfortunately, the writing contains numerous examples of “telling not showing.” (The former is considered a more amateur and less compelling form of writing, as in “he was sad” instead of “he broke into sobs.”)

So, overall, some adults may like this revived classic, and a few deep-thinking teens who like history, philosophy and Japanese culture may read it to the end. But, however, as much as the translator and publisher believe this is a gift from the past and a way to turn contemporary pre-teens on to ethics, those of us in touch with today’s teens can only shake our heads and wonder.

Pam Withers is an award-winning author of 22 young-adult sports and adventure novels, including Mountain Runaways. She lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, and is founder of www.YAdudebooks.ca.