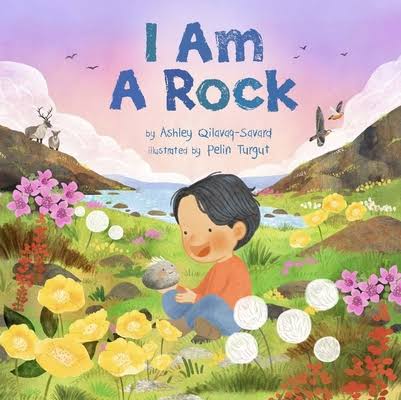

I Am A Rock

I Am A Rock

“Anaana, can Miki Rock feel anything?” Pauloosie asks after a big yawn.

Yes, I experience spring melt, and the soft snow

that blankets me.

I feel the joy of the sun’s warm kiss,

and the cold Arctic breeze brushing by.

I feel happy as the land breathes brilliant

colours around me.

I am excited for the ground to freeze because it means

the mountains will be sprinkled with snow,

and shining rays of light will make the ice glisten.

I patiently watch as the sun says goodnight,

to dance and sing through the northern lights.

I am a rock.

I watch, I hear, and I feel life on the land

time and time again, until one day you pick me up

and bring me home.

With you I can fly,

I can run,

and I can walk.

I am your rock.

I Am a Rock honours the seasonal cycles of Nunavut through a loving bedtime conversation between a child, Pauloosie, and his Anaana (mom). Pauloosie has a pet rock, Miki Rock, at his side as he snuggles under downy blue bedcovers. He asks his mom, “What would it be like if rocks were alive?”

Pauloosie pretends that Miki Rock can describe what he experiences though it is his Anaana who speaks for Miki Rock:

I am a rock.

I do not fly.

I do not run.

I do not walk.

I live on the shoreline, and I get to watch as the water ebbs and flows.

Through Miki’s eyes, readers glimpse the richness of Nunavut harvesting seasons: Miki sees “clams, berries, and running char” and witnesses “seasons of snow homes, foxes, and Arctic hares” and “seasons of snow geese, eggs, and belugas too.”

Double spreads alternate between Pauloosie and his Anaana at his bedtime ritual and the outdoor spaces evoked by Miki Rock’s descriptions, as voiced by Anaana in her version of a bedtime story for Pauloosie. The little boy becomes sleepier and sleepier as Miki Rock recounts what he experienced outdoors before being Pauloosie’s own rock.

Turkish illustrator Turgut creates a cozy bedroom scene with the adorable Miki Rock who has a sunny smile painted on and tufts of hair attached to his head. When Miki Rock describes what he sees, feels, or hears, nature scenes unfurl, with Miki emerging into view during the snow melt or smiling as he sits on the tundra and hears “every sound right here on the ground”, from wolves, herds of ruminants, or “little lemmings too”. Turgut purposefully employs a more rounded, though still naturalistically faithful style to depict animals while evoking the sweeping majesty of the Nunavut landscape studded with bright flowers through the seasons and its stark, cold waters and endless night skies.

Miki Rock’s narrative ends with him describing what he feels: awe at the sight of the Northern Lights, excitement as the ground freezes and mountains receive sprinkles of snow, and joy during spring when the sun warms his face at last. By this point, Pauloosie is asleep, and his Anaana tucks Miki Rock next to him and kisses Pauloosie goodnight.

Lyrically naming the myriad beautiful animals and plants, the turning of the seasons, and the ways in which the world provides sustenance and joy for the Inuit people makes for the perfect lullaby. Aside from attuning readers to nature through Miki Rock, Qilavaq-Savard sweetly shows a child initiating an imaginative exercise that allows for intergenerational transmission of knowledge through storytelling. Each child who reads or listens to I Am A Rock enters that same narrative space and can accept the story’s implicit invitation to be someone with the sense of wonder and imagination to understand what it’s like to be part of the steadfast cycles of the natural world. Unsurprisingly, this picture book makes for a soothing and evocative read-aloud and, with its glossary of Inuktitut words at the back, also offers classroom opportunities for learning more about the splendor and delicate beauty of Nunavut.

Ellen Wu reviews books for CM from Vancouver, British Columbia.