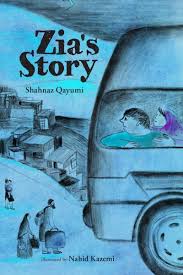

Zia’s Story

Zia’s Story

After dinner I played chess with Pader. Then I went to bed happy because tomorrow was Friday, jumah, our day of prayer, when we would go to my grandparents for lunch or visit my uncles and aunts—or my father’s friends would drop by to chat and drink tea. I thought about what happened that day, the kite fight, the chase, the old man in the garden and what my parents said about the Afghan custom of giving refuge.

Suddenly there was a loud and persistent knocking on the front door. “Open the door!” From the stairway landing, I watched Pader open the door halfway to see who was there. Mother stood behind him.

The door flew open. Three soldiers holding guns and two men dressed in suits pushed their way inside.

“Salam, Khairat ast. Good evening. Is everything all right?” Pader asked.

“We need you to come with us.”

“Why? Did I do something wrong?

“We can’t talk here. You must come with us.”

Moder froze, then broke down crying

The soldiers took Pader’s arms and pulled him outside but he asked them if he could have a word with me. “I want to say goodbye to my son.”

Just for a minute,” one of them said. “We don't have time to wait.”

I walked down the stairs and hugged him tightly. Pader looked deep into my eyes and whispered, “You are now the man of our family, Zia. Until I return home. Take care of your mother.”

I never shared that moment with anyone, not even with Moder. It is a secret between Pader and me.

Based on the experiences of the author and her son, the story is narrated by Zia, a young Afghani boy. The book is set in the time period after Russian troops leave Afghanistan when the Taliban take power in the mid1990s. Zia’s life falls apart when soldiers arrest his father who is never seen again. Simultaneously, the country falls into chaos with frequent acts of violence and the restriction of basic liberties, especially for women and girls who are forbidden to work or go to school. Zia is now the man of the house and must earn a living. Undergoing further hardships, he and his mother seek freedom in Pakistan and later Canada. Even there, he can never forget the country of his birth.

Paralleling the story of thousands of families in Afghanistan both then and now, Zia manages to convey the sharp contrast between his family’s previous happy life, replete with rich cultural traditions and courtesies, with the dire misery to which his life is now reduced. But he also demonstrates his family’s resilience and determination. They retain their integrity and honour while striving for freedom and education.

The storytelling is direct, almost impassive, a foil for the daily dramas that require little emotional embellishment. These include not only the loss of Zia’s father but also the disappearance of friends, a tense escape to Pakistan, the theft of savings and Zia’s mother’s illness. Horrendously, Zia’s ‘free’ education offered in Pakistan is in reality a training school for the Taliban, from which innocent children, like his friend Timur, are sent on ‘special missions’, including suicide bombings.

The angular shapes and black and white tones of Kazemi’s somber illustrations reflect the mood of the story and are rich in detail. Qayumi’s text is enriched by a sprinkling of native vocabulary, many of the words being explained in the text, but a glossary would have been welcome.

Because of the sadness of the story, children might not gravitate to Zia’s Story on their own. However, it is an eye-opening and worthwhile title that will provide children aged 9-12 with much food for thought and provoke many questions. Ideally, it should be shared with an adult for fuller understanding and would be a welcome addition for schools and public libraries. A substantial history of Afghanistan from the Soviet Union’s invasion until the present day is included as back matter, providing background as to how Zia’s situation came about.

Aileen Wortley is a retired children’s librarian from Toronto, Ontario.