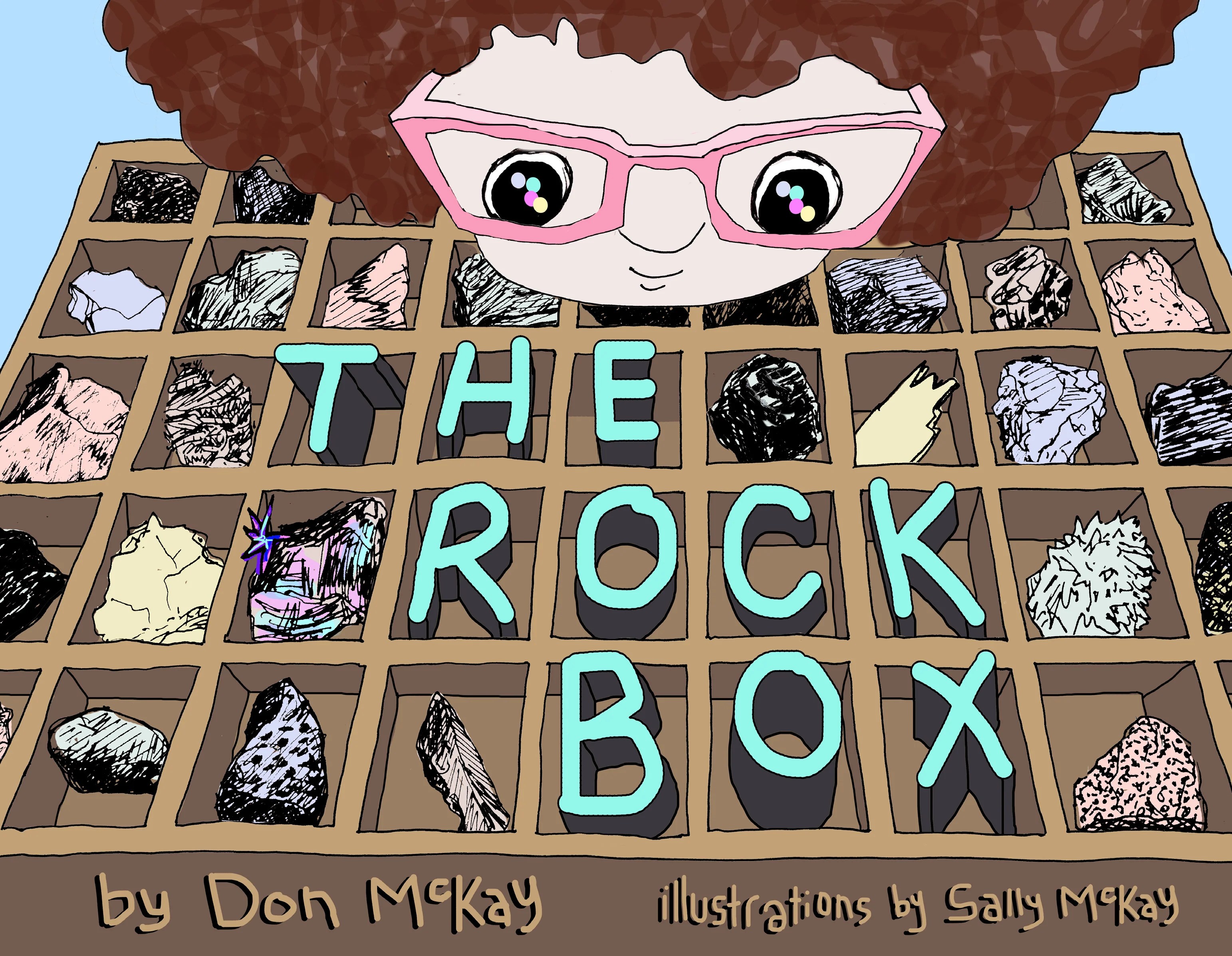

The Rock Box

The Rock Box

Petra’s rock collection is taking over the house! Her parents suggest that she could save just some of her favourites and put the others back where they came from. The idea does not appeal to the girl. In fact, Petra suggests a family road trip to new areas so that she could find even more different rocks. She uses the information she has gleaned from her book, Geology of Newfoundland, to expound on how the rocks to be found in each area of the island differ, but she has yet to convince her mother and father that actually travelling to see and touch them is what they should plan to do.

Negotiations seem to have reached a stalemate. Then Petra’s mom offers her a special gift: a Rock Box. She says:

“See, each specimen has a number, with a little cubicle of its

own, and there’s a booklet telling its name, and something

about it, like what it’s made of. It’s also sort of an antique,

since it’s over 50 years old. I know, not old in rock years,

but old for us humans.”

A similar Rock Box was actually used as a teaching tool in Newfoundland schools in the 1960’s and 1970’s in a project organized by the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Mines, Agriculture and Resources. Petra is entranced with hers, and she spends hours examining the box’s contents and reading the booklet.

At last a summer vacation does take the family on a rock hunt to the Bonavista Peninsula. Mother, father and especially Petra are able not only to find interesting rocks there but the sites of some fascinating fossils, too. There is a little drama when Petra realizes at bedtime that she has taken the Rock Box, which she had brought on the trip for purposes of comparison, out of her backpack and left it behind at a place she had been exploring.

That night was the worst night Petra had ever spent.

Toss, turn, scrunch up, stretch, turn, toss, get up, go to

the bathroom, pee, stretch, scratch, toss, turn.

Petra tried to stop thinking of her poor Rock Box out there

in the rain and wind, and to stop replaying the scene in

her head, this time putting it back in her backpack before

rushing down the trail.

The Rock Box is retrieved, found at the trailhead guarded by a very large toad. The girl’s musing about the appearance and significance of the toad leads to a long, involved dream sequence in which the Labradorite specimen in the Rock Box comes to life.

“Hummergaroo clickclackracketygackety

garoorum,” said the Labradorite,

continuing to wink and hum.

The stone begins to talk and offer up some philosophical thoughts on rocks and the history of the earth, more or less ending the story.

The book is the work of author-poet McKay and his daughter, Sally, who is an artist and educator. The dense, detailed text is packed with information, suggesting that it be put on the science shelves rather than in the storybook area. The characters who drive the narrative speak in a natural way except possibly for their extensive use of word play. (As well as Newfoundland often being referred to as The Rock, the name Petra is from the Greek for rock, which the main character makes a point of mentioning.) However, the attempt to add interest to this plethora of facts about rocks and minerals using a story framework falls short. Extraneous exchanges between the parents and the child, and passages with the talking rock that have been overextended, taking up eight pages, may make readers put the book aside.

Back matter consists of footnotes on the genesis of the Rock Box project as well as a few other names mentioned in the text. There is also a dedication to audio artist Chris Baines who has produced documentaries on the geology of Newfoundland.

Public and teacher librarians will find it hard to place The Rock Box on the right shelf or in the hands of the right user. The Rock Box labours as a story, but it may be of interest to young readers interested in geology.

Ellen Heaney is a retired children’s librarian living in Coquitlam, British Columbia.