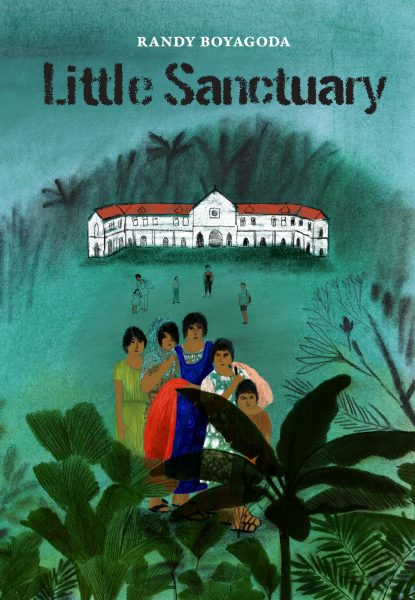

Little Sanctuary

Little Sanctuary

“No one knew. It was the kind of question they were all learning not to ask. What other questions were there? What answers? Sabel had stayed with the adults in the kitchen while the rest of the children played under the trellis behind the house. Eventually the kitchen became quiet. She could tell she was not wanted there, inside, listening to adults asking questions no one could answer. Amma should have told the other adults that even if Sabel was only sixteen, she was old enough to stay with them. But Amma didn’t tell them that. Instead, Amma told Sabel to “Go watch the others and make sure they don’t go down to the gully.”

...

For a moment, Sabel was amazed and reassured that she suddenly had such command over the situation. But these feelings went away after the militia men outside turned from the bus and walked away.

Where are they going? Sabel thought as the crowd filled in the space around the bus. The people looked the same as the ones they had seen in the Old City. Tattered, bundled, tired, limping to the harbour, wearing and carrying and pushing and pulling everything they had left. Children sat on shoulders, and babies were wrapped and strapped to chests and backs. It was an inky, cloudy day, but everyone looked like they were squinting against the sun.

“Someone else needs their help,” said Reya. “Look over there.”

In a dystopian world that is slowly but surely falling apart, a group of children must be self-sufficient and stronger than they could have imagined. Their well-do-to parents sent the children in the family to an abandoned school on an island, presuming it would be a safe space until they could return home. But once there, the children lose faith in those who are supposedly guarding them, and even their sanctuary becomes threatening. While it may be no worse than home, it doesn’t seem to be any better. The children leave this first sanctuary only to find out that there is really nowhere they can be safe. There is, truly, little sanctuary for them.

Randy Boyagoda paints a picture of a dismal world, one torn apart by plague and the collapse of government and society, itself. In this “falling down world”, Sibel takes charge of her siblings and shows herself to be resilient and resourceful in a time when everything appears to work against her. The other children do their best, but all of them quickly learn that gangs, distrust and bribery are the new societal rules.

The novel shows readers two sides of the conflict story and forces some difficult questions. How would you react if you were in control? Would you take bribes and enforce your will upon weaker people, even if your conscience was bothering you? Would being part of the ruling group be important to your self-esteem and allow you to do whatever was asked of you? Could you face the pressure of not going along with your peer group?

And what of the refugees? Boyagoda’s refugees are children, but the book shows that the parents/adults in the story, as well as the children, are powerless. The children have been jabbed and had their hair cut to hopefully avoid the plague and have been sent to a place of supposed sanctuary, but, in the end, very little can be done when society has been upended and all of the old norms no longer exist. Do you continue to work as a group, or does the inherent need for self-preservation take precedence? What would you do? How far would you go to survive?

Boyagoda does not sugar coat his story nor does he provide a “happy ever after” ending to the book. Little Sanctuary is a timeless story about good versus evil and seems especially poignant after enduring the Covid epidemic as well as hearing countless stories of war-torn countries and refugees on the daily news. Little Sanctuary may not be entertaining, but it is surely thought-provoking.

Ann Ketcheson, a retired teacher-librarian and high school teacher of English and French, lives in Ottawa, Ontario.