The Hippie Pirates

- context: Array

- icon:

- icon_position: before

- theme_hook_original: google_books_biblio

The Hippie Pirates

Ryan moaned. “There’s nothing cool here to explore.”

“Yah. Boooorrrring!” Kent complained.

Amy nodded in agreement with her brothers.

With a chuckle and a sly grin, the hippie pirates looked at their disappointed grandchildren. “Oh me loves, let us tell you a thing or two.”

“If you knew Captain Kidd buried his treasure somewhere in Nova Scotia, wouldn’t you want a chance to hunt for that? How about visiting the birthplace of Canada? Seeing the very building and the very table where the gentlemen sat to sign the document that made Canada, Canada! Just imagine all the Xes we could put on a map of Newfoundland visiting each of the towns that run along a place called Iceberg Alley.”

“Iceberg Alley? Like the iceberg that sank the Titanic? Oh, I don’t want to go there.”

Amy shivered.

“You really are a ’fraidy cat.” Ryan taunted her. (Pp. 53-54)

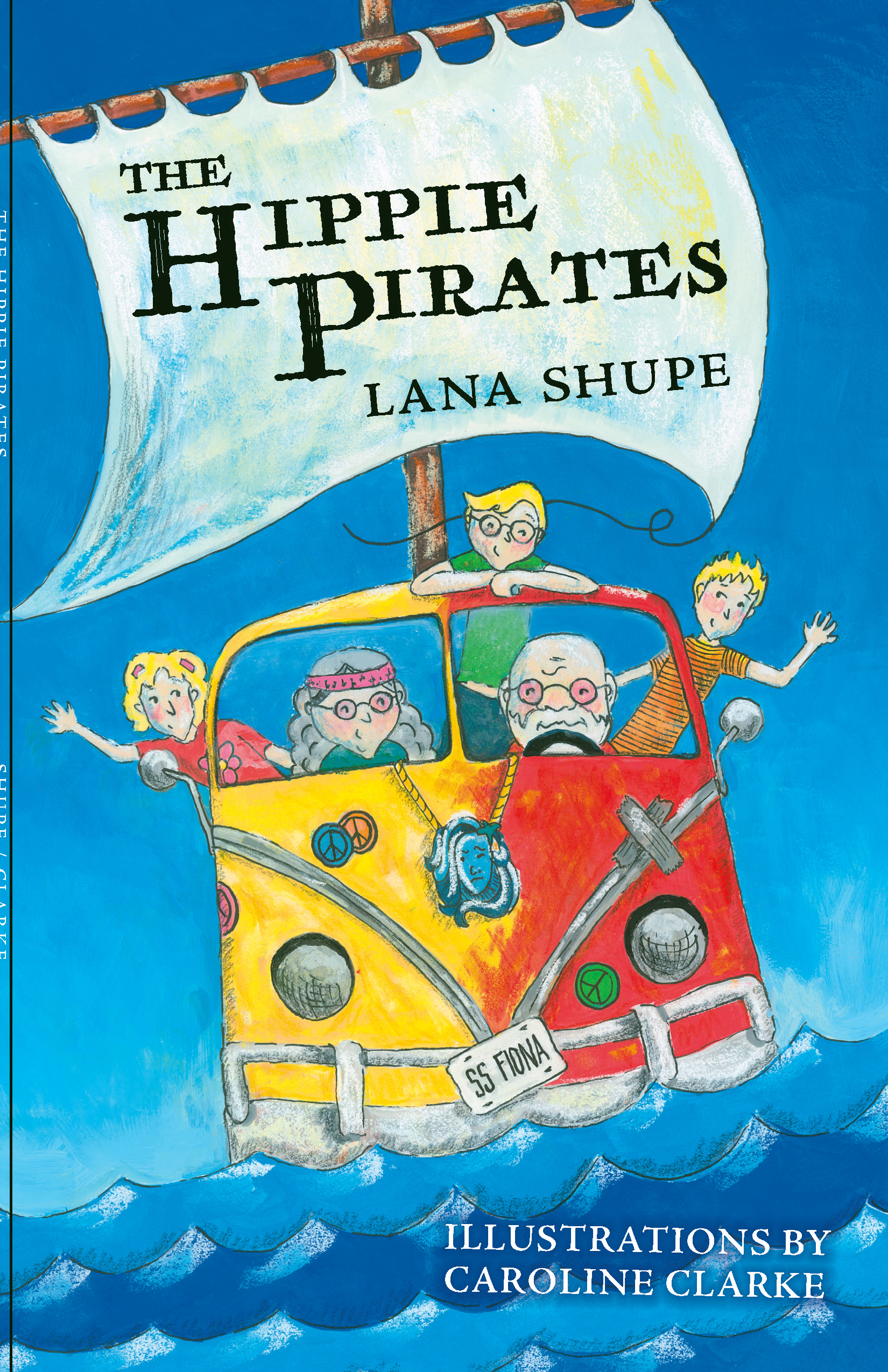

The Hippie Pirates, a junior novel written by Lana Shupe and illustrated by Caroline Clarke, is an adventure story that often misses the mark for its child audience, and its superficial treatment of Canadian Black History is problematic.

Kent, 10, Ryan, 8, and Amy, 6, love to visit their grandparents’ cottage near Shelbourne, Nova Scotia. Their grandparents are known as the “hippie pirates”. The hippie pirates love to regale the children with stories of their fantastical adventures. For instance, they claim to have been chased by a mummy in Egypt, helped the Emperor of Japan and the Queen of England, and escaped a gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Kent, Ryan, and Amy love these stories, but secretly they believe their grandparents have been exaggerating. At the same time, the children accept that the hippie pirates are able to travel the world in a 1963 VW bus and that this vehicle both drives and sails. This makes it a bit difficult for readers to orient themselves at the start of the book and to understand what is supposed to be real and what is exaggerated or fantasy. The illustrations by Caroline Clarke are sweet and whimsical but don’t clarify the situation. For instance, when talking about the bus, the text states: “The children could see the SS Fiona bobbing in the water at the little crooked wharf” while the illustration shows a patched up van that appears to be parked on grass (Pp. 22-23).

A large part of the story is devoted to developing the mystique around the characters of the hippie pirates and setting up the adventure. This is done at the expense of fully developing the characters of the children. Like the child characters, the child reader sometimes feels like an afterthought as the text can be difficult to follow. It often feels very dated in the storytelling and language, including a questionable decision to describe a parrot as “queer looking’” (p. 38) and calling the young girl “bossy”. (p. 78)

The plot of the story centres on the hippie pirates taking their grandchildren on their first adventure together. The family travels back in time to Shelburne, Nova Scotia, in 1785 to learn about the Afro-Nova Scotian Loyalist community. While this is an excellent topic for a time travel book, the execution is lackluster. The story does not adequately engage with the historical subject matter it introduces. Most of the historical information is relayed when the grandparents encourage the children to do research before the trip. The three seemingly white children learn about the history of Black Loyalists and recite their research back to their grandparents (and the reader).

Once the group finally goes to Shelbourne in 1785, they meet a young Black boy named Samuel who tells them he has to return to Birchtown (the Afro-Nova Scotian community nearby) or risk being chained up by soldiers. It is a fairly brief interaction, and the children decide they can’t really help Samuel. They decide to separate from Samuel without ever going to Birchtown.

For a book that is 14 chapters long, only two of the chapters contain the time travelling adventure. Furthermore, in those two chapters, a large portion has nothing to do with the historical situation and is simply about two of the siblings trying to rescue their brother who has fallen in the water. The end of the book has a section titled “Questions for further discussion”. Most of these questions are about the history of Black Loyalists in Canada, but the answers are not found in the story. If the reader wanted to learn more, the author has only listed one book for further reading.

Overall, The Hippie Pirates centres white voices in Black Canadian history without fully engaging with the important subject area. Disappointingly, the real focus of the story is on building up the hippie pirates without adding much substance.

Beth Wilcox Chng is a teacher-librarian in Prince George, British Columbia. She is a graduate of the Master of Arts in Children’s Literature program at the University of British Columbia.