The Scarf and the Butterfly: A Graphic Memoir of Hope and Healing

- context: Array

- icon:

- icon_position: before

- theme_hook_original: google_books_biblio

The Scarf and the Butterfly: A Graphic Memoir of Hope and Healing

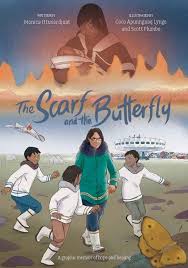

On the cover of The Scarf and the Butterfly, an Inuit woman in a bright green parka is surrounded by three smiling children as they walk on the land of a Northern settlement. In the foreground, a yellow butterfly hovers, and, in the background, a brightly patterned white scarf flutters in the air. It’s idyllic, contrasting with the illustrations in the next five pages. Rendered in gray tones, those pages depict a school hallway from decades past in which a young girl in a school uniform, her back to readers, walks past a water fountain to the doorway of a classroom.

The book begins with the story of the scarf and the butterfly. When Monica Ittusardjuat was a 10-year-old, her mother had to be hospitalized, but, before she left, she gave her daughter a beautiful scarf which Monica wore “wherever [she] went to show it off.” (p. 2) One day, she and friends are out on a walk, hoping to catch butterflies. Even though she tries using the scarf to trap one, Monica doesn’t succeed. One of her friends does catch a butterfly, and, when the group of friends gather to look at it carefully, Monica realizes that she has dropped her scarf. Her friends

take off in another direction, looking for more butterflies, leaving Monica to search for her scarf. She finds it, and, as the group of friends returns home, they talk about the events of their day. Everyone is pleased; they’ve found butterflies and Monica has found her scarf.

That is the simple life the author experiences until she is taken to residential school in Chesterfield Inlet. Suddenly, the narrative moves forward in time and place. Monica is in Ottawa “in the opposition’s gallery to hear the Prime Minister’s apology for the residential school system. [She] had waited more than 40 years for this apology”. (p. 13) What was the impetus for that trip to the nation’s capital? Witnessing her seven-year-old granddaughter’s joy at life, singing, dancing, laughing, and always happy, always having fun, reminded the author of her of life before residential school and her sadness at a lost childhood. Monica’s life was not joyful, either at residential school or later in her marriage to another residential school survivor. She admits that her children witnessed drunkenness, violence, and abuse, and that police intervention was frequent. Finally, overwhelmed by depression, one night Monica overdoses on Valium and was saved only when a cousin came to her home and took her to the hospital. Nor was Monica the only member of her family whose residential school past led to alcoholism and substance abuse.

The grief that Inuk families experienced each autumn when their children were taken back to residential school was like a death in the family. Distance made emotional bonds tenuous, and, over time, family relationships could not be repaired. As the author listens to the government’s apology, she is overwhelmed with memories, not only of her own experiences, but of “loved ones who were survivors lost to suicide, murder, and “accidental deaths.” (p. 20)

Then, the narrative returns to the past, recounting the author’s premature birth at the family’s winter camp on the western side of Baffin Island. Both mother and baby are ill, but they survive, and, with their extended family, they live a subsistence life in which the skill of hunters provides for the entire community. At night, the hunters tell stories, sing chants, or play traditional games. In springtime and summer, the community moves, hunting and gathering the fish and animals wherever they camp. The author states that “from the time I was born until I went to residential school in the fall of 1958, I was always learning.” (p. 27) But the knowledge gained from life in her community was very different from what she was taught in residential school, and those traditional life lessons were not valued in that school system.

After Monica Ittusardjuat had attended schools in three different locations, her residential schooling ended in 1969. Whatever knowledge she had gained in school was counterpointed by the shameful realization that she had lost her culture and her identity as an Inuk. One of her strongest memories is of her Grade 5 math class and of a teacher who was “so good at teaching us math” (p. 30), but very impatient with students who can’t provide the right answer on demand. She recalls a terrifying incident in which the teacher’s verbal abuse of the students culminates in his throwing an eraser at a student, injuring her. Then, the narrative returns to the author’s participation in a hearing at a “claimant-centred, non-adversarial, out-of-court process for the resolution of claims of sexual abuse, serious physical abuse, and other wrongful acts suffered at Indian Residential schools.” (p, 33) Remembering that incident stirs up feelings of intense self-loathing and a return to self-destructive activities from her past. At the sam

she tries to make sense of the behaviour of the teachers at residential school: “What is it that makes them want to dominate, control, manipulate, and judge those who are not like them?” (p. 34)

Years after the math class incident, Ittusardjuat attends a healing retreat where one of the exercises has participants deal with their responses to authority figures. The author is asked to imagine that she is back at school and is called to the office. The black and white images of the school hallway, featured in the book’s opening pages, are now colourized, and we see her as a student, eyes downcast, walking down the hall, full of shame at her inability to understand the rules of life as a Quallunaaq (i.e. a non-Inuit). As the exercise proceeds, she describes herself as being in a dark, cold cave, with escape a near-impossibility. She realizes that she “was stripped of [her] identity and there was nothing of [her] culture left.” (p. 43)

From this dark place, the narrative returns to her life in the North. Readers see her as an adult, smiling as she recounts her love of blizzards, the sound of the wind a comfort rather than a threat. She remembers feeling safe, cuddled by her parents during storms, and of her father and uncles talking and laughing as they prepared for a hunt. For Ittusardjuat, this warmth and security is the essence of Inuit identity. Nevertheless, as an adult, she continues to struggle with her reclamation of that identity, and several pages of illustrations depict her as a young student attempting to escape the dark cave of her inner self, carrying a terrible burden, hoping that she can find the necessary help to become the person that she wants to be. It’s a lifelong journey, and she states that she “is still stacking rocks, trying to get out of the cave”. (p. 53) It is a personal process, but she concedes that she needs assistance in order to gain confidence, self-worth, and the opportunity to “accomplish good things for [her] people.” (p. 54)

At present, Ittusardjuat lives in Toronto, engaging with as much of her Inuit culture as is possible in that urban environment. Her schooling in non-Inuit culture has left its mark on her, and she recognizes that she is different from other Inuit friends or family. Ittusardjuat concludes her story with a statement of optimism and hope, asserting that she has not been broken by the adversities that she has faced. As the book moves to its conclusion, readers are offered two portraits: one is of Ittusardjuat as an adult, and one of her as a child, wearing the scarf her mother gave her, with a butterfly in the corner of the portrait. The final piece of text is “A Reflection on the Pope’s Apology”, an apology made during Pope Francis’ 2022 trip to Canada during which Monica Ittusardjuat had a private meeting with the pontiff. It’s clear from her reflection that she is dissatisfied with the apology and that the words of it are not enough. Following her reflection is a page featuring two uncaptioned photographs depicting protest at the papal visit. Many readers would not know the significance of the words on the placard reading “Recind [sic] the Doctrine of Discovery” nor of “Facta non Verba”, and captioning would provide a context and reference to her reflection.

The Scarf and the Butterfly> is a publication of Inhabit Education’s Qinuisaarniq (“resiliency”) program, designed to educate the Nunaviummiut (those who inhabit Nunavut) about residential schools, policies of assimilation, and colonial actions in the Canadian Arctic. For Monica Ittusardjuat, residential school was soul-destroying, leaving her with powerful feelings of inferiority. Her memoir relates the experience of many Inuk, yet it is also deeply

personal. Memory is never purely linear, but I believe that the story would have been more successful had it been chronologically organized, rather than moving back and forth between her memories of the past and the present. Monica Ittusardjuat has suffered greatly from being taken from the security of her family and community, and the legacy of her residential schooling is a disconnection from both Inuit and Quallunaaq society. Hers is a lifelong struggle, and she is honest about her setbacks, but she has persevered and continues to do so.

The illustrations rendered by Coco Apunnguaq Lynge and Scott Plumbe bring an added dimension to the story. Their use of colour skillfully conveys both the strong sense of community amongst the Inuit and the bleakness of residential schooling. However, I believe that the graphic novel format was not the best choice for telling this story. The content of the text boxes is much lengthier than is typical in a graphic novel, and the typeface is not easy to read. In many graphic novels, the text boxes contain dialogue which moves the story along. In this memoir, the dialogue was often “interior”, reflective of the author’s thoughts and memories, and at times, the content was repetitive.

Ittusardjuat’s story contains a selection of Inuktut words (i.e. the word for Inuit languages in Canada), and the “Inuktut Glossary” provides both a translation and a pronunciation guide for those words appearing in the context of the story.

The intended audience for this book is Grade 9+, and the references to events such as the Prime Minister’s apology for the residential school system, the Independent Assessment Process of the Federal Government, and concepts such as “core identity issues” are unlikely to be familiar to readers younger than that age. For that matter, they may also be unfamiliar to older readers and would necessitate some background work. Although much has been written and published about the Indigenous experience of residential schools, The Scarf and the Butterfly has value in offering a perspective on the Inuk experience. However, the non-linear narrative makes this less than easy reading. The Scarf and the Butterfly is worth considering for acquisition as a supplementary work in social studies classrooms and for school libraries in Canada’s north.

Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 Territory and Homeland of the Métis People.