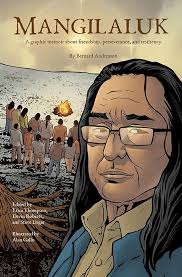

Mangilaluk: A Graphic Memoir About Friendship, Perseverance, and Resiliency

- context: Array

- icon:

- icon_position: before

- theme_hook_original: google_books_biblio

Mangilaluk: A Graphic Memoir About Friendship, Perseverance, and Resiliency

Some children are born into the world and are home as soon as they come Earthside.

Others spend their lifetimes searching for a home, a place to belong, a place where they are safe.

I am one of those children.

After spending the first two years of my life moving from one unsuitable home to another, I was given to the Andreasons. Maybe they would be able to love and care for me in the ways that a child should be loved.

Maybe. (Pp. 6-8)

But for some reason, the Andreasons rarely made Bernard feel cared for and loved. Sad memories – sleeping outside under the house while his parents and friends drink and party – dominate, and, after six more years with them, Bernard leaves Tuktoyaktuk to attend Stringer Hall School in Inuvik.

At the school doors, he is greeted by a priest and a nun, both of whom are stern and intimidating. The students at Stringer Hall sleep in barracks-like dorms, and, in the illustrations of the classrooms, no one looks happy or engaged with learning. “Shame and fear were sharp weapons” (p. 17), and the punishment most feared was “the pole”. The student who was deemed “naughty” was forced to stand holding onto a pole in the middle of the cafeteria while the rest of the students were allowed and encouraged to taunt him.

Still, Bernard makes friends, and Dennis and Jack become his best buddies. At times, they get cigarettes, sneaking out to the end of the schoolyard for a smoke. One day, they are out of smokes and decide to steal them from the dorm supervisor. Because the punishment will be worse than the crime, they decide to leave school and just take off. At first, the journey is a lark. They’re free, certain that they can find their way home, forgetting that they arrived at the school by airplane. When they arrive at a raging creek, Bernard wants to return, but his friend Dennis decides to chance a crossing. Bernard and Jack leave him there, but the weather turns treacherous, night falls, and they can’t find Dennis. The two decide to walk to Inuvik, but Jack is sick, and, in the illustrations showing the physical struggle to continue, Bernard also struggles with indecision as to what they should do next, a difficult situation for an 11 year-old. He “get[s] tough with Jack, thinking that [he] could scare him into coming with [him].” (p. 40) When Jack won’t go, Bernard leaves his friend and forges ahead, alone and afraid.

Bernard walks for kilometres, following the power lines leading to settlement and assailed by swarms of flies and unbearable guilt. Rescued by a pair of hunters, he is flown home. Unprepared for the lengthy trek that he undertook, he needs to recover from physical and emotional stress. For awhile, he feels comfortable within his family circle, even though he is profoundly saddened by his abandonment of his two friends and the knowledge that they are gone forever.

Although a good student, Bernard never felt good enough at Stringer Hall. Inexplicably, although his relationship with his foster parents is again strained, he does not return to Stringer Hall. At school in Tuktoyaktuk, he is bullied and ridiculed as “the kid who ran away, that kid who survived, that kid who didn’t seem to belong anywhere.” (p. 52) Years pass, home life deteriorates further, he becomes an alcohol user and, more than anything, experiences a deep and profound loneliness. He attends school less and less, and, when he does, he underperforms. High school is no better, and, finally, he decides that, if he is to have any hope of a better life, he must leave Tuktoyaktuk. Guilt over his friends’ fate weighs heavily on him, but it also motivates him to find a new path. After several years of drifting, he enrols in the Indigenous Journalism program at Western Ontario in London. Ontario.

At Western, and for the first time in his life, Bernard feels accepted and a part of a community. The negative forces which had limited him – family, residential school, abuse of all kinds – are absent, and he believes that he will have a very different future. However, in the 1990’s, HIV/AIDS was an omnipresent threat and, once diagnosed, Bernard “felt judgement everywhere” (p. 63) and leaves for Vancouver. Life in Vancouver is a struggle; he lives on the streets or wherever he can find shelter. A compassionate doctor provides both the drugs which help to manage Bernard’s illness as well as connection to social services which provide him with some necessary financial stability.

Once life settles, Bernard revisits his desire to continue his education, and he enrols at Vancouver’s Native Education Centre (NEC). From the welcoming ceremony of his first days to the ongoing supports which the staff and other students provided, NEC is a life-changing experience, and, at age 38, with the completion of an Adult Upgrading Program, Bernard decides to move to UNBC in Prince George. While the campus, itself, is beautiful, the social atmosphere isn’t. Living off campus, and commuting every day, he lacks the connection he had at NEC. He faces racism, difficulty in obtaining necessary medications and lack of the supportive medical care he had in Vancouver. When his family sends news of the death of his biological father, Bernard wrestles with whether or not to go home. Although he “had never felt valued or accepted at home, . . . family is family, and when you’re needed you go.” (p. 73)

All seems fine at first, but soon, all the negative patterns of family interaction resurface. While his family claims to be grateful for his stepping up at the time of loss, they also question the value of his academic studies. After being away from school for five weeks, Bernard has missed classes, is running low on medication and worries that he will be evicted from his apartment. His fears are well-founded. He remains in Prince George for more than a decade, eking out a living, never returning to university, always knowing that HIV/AIDS has shortened his life. Haunted by memories of his family’s rejection and the loss of his school friends when he was 11, he returns to Vancouver “in the same situation [he] had been in at 31 years old: broke, homeless, and in fear for [his] life.” (p. 84)

Once back, he reconnects with Dr. Catherine Jones, the compassionate doctor who first assisted him, finds decent housing, and goes to the Dr. Peter Centre, a community founded by a physician who was himself an AIDS patient. Bernard had finally found the safe place he had sought throughout his troubled life. The Centre assists residents with social supports and services, values the gifts and talents of all individuals, and respects Indigenous culture. He is now ready to share the painful stories of his past, including the traumatic escape attempt from Stringer Hall. An opportunity comes when a young teacher of grade 9 English in Inuvik contacts Bernard, asking him to meet with his class. That class has been reading the story of Chanie (Charlie) Wenjack’s fatal escape attempt from a residential school near Kenora, Ontario. The young teacher wanted his Inuit students to learn of their history and of a similar story, one based locally. As well, there are hopes and plans for holding a ceremony which would honour Bernard, Jack and Dennis, offering prayers for them and their families.

Bernard thought long and hard about having to return to Tuktoyaktuk and revisiting a long-ago trauma. Although it might undo the healing he had undergone, he saw potential for teaching the students a lesson about change and resilience. So, he went. The warmth, solemnity, and joy of the honour ceremony are depicted in a series of wordless frames, and, in the second last frame, we see a strong and happy man:

I felt the power of their prayers over me and the admiration of all these people who felt I had lived a life worth honouring. I felt my story come alive, and I felt a weight lift from my shoulders. . . I heard the beat of a song I hadn’t heard in decades: the song of my ancestor, my namesake – Mangilaluk. I stood in my new atikluq* and slipped on the leather gloves that male dancers wear, and I danced among them. And I healed. (p. 94)

[*an atikluq is a hooded pullover summer shirt]

Mangilaluk is the story of an Inuvialuit man who endures a life of guilt, loneliness and isolation, starting with rejection by his adoptive family and continuing with abusive behaviour at residential school, stigmatization as an HIV/AIDS patient, poverty and racism. Bernard’s attempts to educate himself are frustrated at various times in his life by a variety of negative forces; for every two steps forward, there is one step back. But it is also a story of survival against the odds and the hope that an individual can heal from a life of emotional barrenness.

Mangilaluk is a graphic novel in which the most powerful episodes are depicted in the book’s wordless illustrations: Bernard’s taking a blanket and bunking down under his family’s house while the adults drink and party; his arrival at Stringer Hall and spending a lonely Christmas at the school; and the terrifying journey the three boys take to escape from residential school. However, the font used in the text frames is rather small and not easy to read, especially in the lengthier sections of text.

I was curious about the illustration in which Bernard is met at the door of Stringer Hall by a priest and a nun. Stringer Hall was run by the Anglican Church. While there are female religious orders in the Anglican church, were they involved in missionary work in Canada to the same extent as were Roman Catholic nuns? The illustration suggests so, but, if nuns were not involved in education at Stringer Hall, it is unfair to suggest that they were.

Mangilaluk offers another perspective on the Inuit experience of residential schooling and of the foster care system. It is a story of resilience, courage and healing and worth obtaining for high school libraries and as a parallel work for classes reading the story of Chanie (Charlie) Wenjack. Wenjack’s tragic death resulted in national attention and sparked an inquiry into the treatment of children in residential schools throughout Canada. Mangilaluk is the story of a man who tried to escape and survived.

Joanne Peters is a retired teacher-librarian who lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 Territory and Homeland of the Métis People.