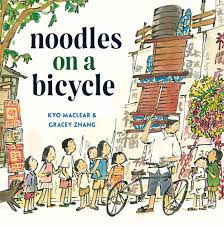

Noodles on a Bicycle

Noodles on a Bicycle

When the deliverymen cycle through the neighborhood,

we want to see them.

We want to be them.

We give it a try.

We pluck one of our bikes from the shed.

Squeaky seat and rusty chain.

We carefully practice stacking trays

with bowls filled with water.

With the rapid modernization, urbanization, and technological advances in contemporary society, some communities fear that young people are losing touch with their historical heritage as they grow increasingly farther removed from it, due to their lack of direct experience and emotional attachment with that past as well as the loss of the people who have preserved those stories and experiences for future generations. Despite these developments, some communities have achieved success with preserving and even revitalizing their heritage, but some stories, activities, and traditions have become irrecoverably lost due to the passage of time. One such experience that people can no longer experience first-hand is the opportunity to see deliverymen who delivered soba noodles by bike and balance towering trays on their shoulders, something that would have been a common sight during the 1930s to 1970s in Japan.

Kyo Maclear’s Noodles on a Bicycle renders this historical era successfully with its vibrant and moving narrative about deliverymen, known as demae in Japanese, who toil endlessly to deliver food to their customers throughout the year. In doing so, she documents these demaes’ labour in an appealing manner for young readers while, at the same time, capturing the perceptions and experiences of living as a child in Japan.

By representing these demaes’ work from the perspective of young children, Maclear instills a sense of immediacy to their experiences, thereby contributing to the story’s emotional impact and drawing readers into that historical era. This choice of narrative technique also frees Maclear from the constraints of a more measured adult perspective and allows her to leverage the freshness of viewpoints that become possible from young children who may perceive their surroundings in an uninhibited manner. Gracey Zhang’s accompanying illustrations enhance the book’s tone while, at the same time, depicting its characters’ feelings effectively.

The story captures the children’s sense of awe about the demae whose work they admire. To the children, the deliverymen are larger-than-life individuals whose seemingly magical acrobatic skills allow them to navigate deftly through the busy streets with their towering stacks of bowls and boxes for their customers, never spilling or losing anything prior to their arrival. The children become inspired to emulate them, even though they do not wholly succeed in balancing their bowls and trays. Conveying respect for the demae and their long hours of work, the story emphasizes their rigorous and unflagging work ethic. While other people may finish their jobs before dinner and wind down for the day, these people are still working late into the evening in order to feed their customers. Despite the demanding physical nature of their work, these deliverymen fulfill it with an unflappable sense of grace and dedication that emanates through the story’s text and illustrations.

Zhang’s illustrations complement Maclear’s text effectively. The illustrations use a technique of exaggeration to highlight the deliverymen’s dexterity and formidable strength. In the first illustration of a deliveryman, Zhang shows him taking off on his bike with his stack of ceramic soup bowls and wooden soba boxes flying behind him. The illustration is not meant to be a realistic portrayal of this activity as the stack of bowls and boxes are slanting almost horizontally to the ground, which, in real life, would have them crashing to the ground. However, in this case, the illustration conveys the deliveryman’s speed and adroitness in keeping his wares balanced for the whole trip.

Besides building on specific moments in the plot, Zhang’s illustrations enhance readers’ experience by depicting historical Japan effectively. Her attention to interior and exterior details add authenticity to these illustrations, convey the settings’ cultural atmosphere, and contribute to their immersive impact by facilitating readers’ ability to visualize these scenes. For example, her illustration of the children’s home suitably conveys a Japanese household with her representation of its decor as well as the inclusion of readily identifiable objects such as soy sauce, a wok, and other items. Exterior scenes contain details, such as storefronts with signage in Japanese, architectural elements evocative of the historical era, and the well-known Sa’nai tower with the Mitsubishi logo that has existed over six decades ago. The people populating these scenes are wearing clothes that evoke the historical era, including students in their school uniforms, women wearing traditional kimonos, and white-collar workers in suits and other formal business wear. Similarly, the vehicles drawn in this book also derive from models of the 1950s and 1960s that Zhang discovered through her research. These included the three-wheeled trikes with car engines that circulated in Japan during that time before disappearing in the 1970s. Adding to the book’s sense of authenticity is Maclear’s inclusion of two historical photos that show soba noodle deliverymen in Tokyo back in the 1930s and 1950s.

Inevitably, writing about the past comes with its challenges, particularly when authors have a personal and positive connection with the past that they are writing about and may romanticize it or filter it through present sensibilities, whether in an unconscious or deliberate manner. As a result, their writing may represent that past in a way that may not align with “reality”. At the same time, these inclinations are unavoidable due to the distance between the past and present, such that the past can only be interpreted through the lens of the present. Even when a story is based on first-hand experience, the past is something that can only be recollected through memories and reconstructed in the present time, regardless of how objective an author may aspire to be.

To a degree, an element of nostalgia permeates the book, a feeling which is enhanced by its suggestively whimsical language and poetic writing style. In addition, the text’s placement on the page contributes to its poetic tone. Throughout the story, individual lines of text are laid out and grouped on the page in a deliberate manner that visually mimics the appearance of poems. Besides giving readers the impression that they are reading a series of short poems, the arrangement of the story’s text also allows readers to move fluidly from one set of lines to another. For example, the spacing between the story’s first four lines of text contributes to a lyrical mood that aligns with the story’s overall tone.

However, Noodles on a Bicycle is not simply a contemplative musing about an irrecoverable, bygone era, but rather it’s a celebration of past experiences that are worth remembering and documenting for people to enjoy. Drawing upon her memories and information from her research, Maclear created this narrative. At the end of the story, there is an “Author’s Note” that reveals the story’s personal resonance for the author. During her childhood, she would spend her summers in downtown Tokyo where she would personally witness these deliverymen on their shifts. However, Maclear did acknowledge that, during her childhood, times were starting to change as the method of soba delivery was already changing, since the sight of demae on bicycles was becoming rarer and was being replaced by people on motorcycles. Although noodles are now delivered in more efficient ways, she also affirms that there is something magical and innovative about the “old days” that is worth remembering and celebrating, including the demaes’ “use of clean transport and reusable bowls (no plastic bags or Styrofoam containers)—and their great circus-like magic.”

Noodles on a Bicycle will be a valuable addition to libraries that want to develop their collection of books about Asian communities in Canada and abroad, particularly stories that pertain to Japan in the twentieth century. Even though the publisher’s website indicates that this picture book is suitable for children ages four to eight, the story will have broader appeal and may interest adult readers since it explores other dimensions of Japan’s history that may be unfamiliar to North American audiences. As a pedagogical text, teachers can use this book as a starting point for generating discussion about the broad topic of documenting and uncovering untold experiences. It could also be used to stimulate students’ interest in the past and encourage them to investigate obscure or forgotten histories and experiences. To approach this book on a personal level, teachers could prompt students to explore and discover stories from the past of their own family, other relations, or even the larger community in which they live.

Kyo Maclear is an essayist, editor, novelist, and children’s author who currently lives in Toronto. Her books have been translated widely and have received numerous nominations, including the Governor General’s Literary Awards, TD Canadian Children’s Literature Awards, and Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards. Her work has also appeared in The Globe and Mail, literary magazines, and other publications. She is also the recipient of the 2023 Vicky Metcalf Award for Young People for her work. Her official website is https://www.kyomaclear.com.

Gracey Zhang is an award-winning illustrator, author, and animator. Originally from Vancouver, she is now based in New York. She received the Ezra Jack Keats Illustrator Award for her debut picture book, Lala’s Words (www.cmreviews.ca/node/2715) as well as The New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book of 2022 for her illustrations in The Upside Down Hat (www.cmreviews.ca/node/2986). Her website is http://www.graceyzhang.com/.

Huai-Yang Lim has a degree in Library and Information Studies. He enjoys reading, reviewing, and writing children’s literature in his spare time.