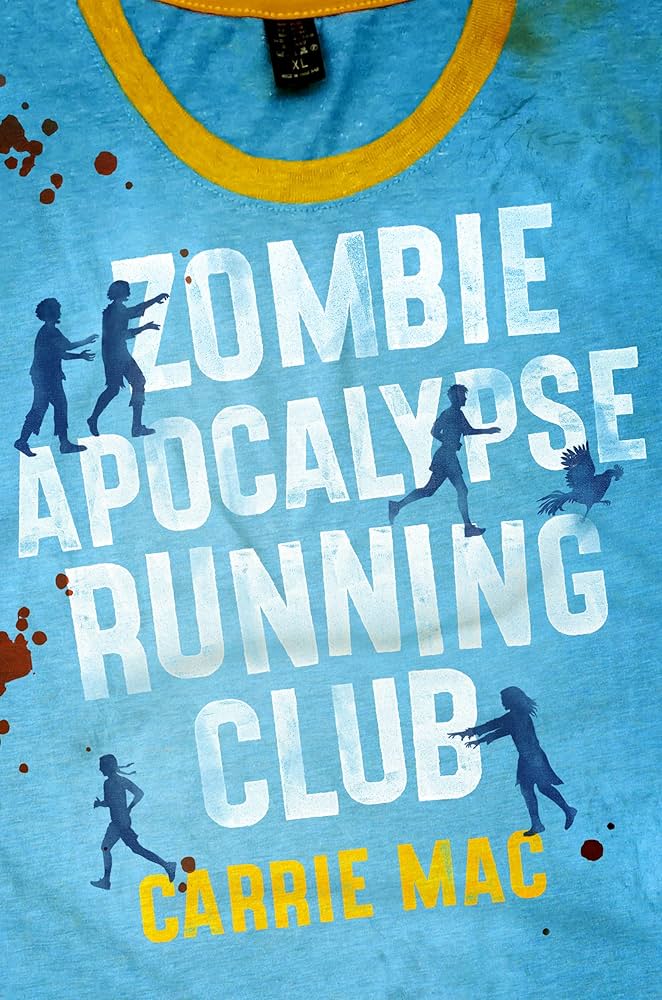

The Zombie Apocalypse Running Club

The Zombie Apocalypse Running Club

“Let me at the zombies,” a tall, scrawny man with zero Ren faire attire on says. “I’d shoot so many of them motherfuckers.”

“Language,” Lola’s dad says. Bersi might be the only person I know who is more Christian than my dad. “No swearing. And no mention of zombies. There are no such things.”

This kills the conversation enough that the talk shifts to the events of the weekend and the setting up of the market stalls and the competition arena and building the bonfire—which is the first one we’ve had in two years because of fire bans.

“That’s cool,” Soren says as we put together the frame of the tall peaked tent that will house our shop at the front and our cots behind the quilts hung across the middle as a divider. “We just have to worry about zombies instead of being burned alive. Actual zombies.” We’ll keep the horses out the back, because we get to put our tent up against a little paddock, given that we’re the Sigurdsons’ closest friends. I am trying not to think about zombies. This will not be another COVID, with quarantines and years of trying to sort out what is bullshit and what is legit, which I didn’t even have to do for myself when we were seven. All I cared about then was when the library would open up. But when you have a father who embraces all the right-wing conspiracies and white nationalism, it is hard to figure out what you think for yourself, no matter what the polarizing situation is. Confusing at first, then deeply disappointing when you start to think for yourself and realize that you’re living with a bigot who would rather see the government topple than have it pay one more cent to health care or any pursuit that could possibly benefit people who are different than you. The list of reasons that it’s time for Soren and me to leave home isn’t all that long, but with a reason like a paranoid, racist, homophobic, xenophobic father, who needs quantity over that kind of quality?

I can easily say that the pandemic is what made Soren and me wake up. Call us woke folk—a slur when Dad says it—or call us liberal sheep (one of his favorites), or simply call us Soren and Eira Helvig growing up and into our very own shiny and independent brains that look a lot different than our parents’ do.

Eira and Soren Helvig, queer twins living with their hyper-conservative family on an isolated homestead, are ready to branch out and start their own lives. They have survivalist skills (drilled into them by their father) and a plan to secure work after leaving their family. Two major problems stand in the way: one, they have to lie to their parents to get away, and two, a zombie apocalypse pandemic is rapidly spreading throughout the world.

Toxoplasmosis has mutated, and anyone infected essentially becomes a zombie. The infected people crave human flesh, and one bite from an infected person rapidly transforms a healthy person into a zombie. In true zombie fashion, in order to kill an infected person, the brain of the zombie must be the target. As if this new reality wasn’t complicated enough, the Helvig twins must listen to their father’s denialism about the infection and face questions of morality and safety in their father’s decisions to protect the land and family. The twins are able to make their escape after convincing their parents that they are just going to check on the family cabin, and they leave everything they’ve known to try to start a new life.

Surviving in the zombie apocalypse isn’t easy, and there are many moments when the twins consider just going back home. Fate, however, decides for them when they find their little sister at a gas station desperately waiting for them. The zombies were able to infiltrate the Helvig homestead, and there is no turning back. Safety and survival become the only goals, and the crew of young adults (now the three Helvig siblings, and Racer, a Special Olympics medalist who insists on upping everyone’s cardio through daily training, hence the title of Zombie Apocalypse Running Club travel across the country on horseback trying to find some semblance of normalcy.

The group meets several challenges along the way—all very normal, trope-y style challenges of surviving zombies after they have cleared out every city—and connect with several different groups of survivors and zombies along the way. There are some graphic scenes of death and zombie killing, but that is to be expected in a fast-paced, apocalypse novel. There are engaging discussion about gender identity and moments of queer connection and love and also characters opposed to the existence of queer joy.

This novel has a deliciously hopeful and heartwarming ending, one that doesn’t feel forced or cheesy or predictable despite maybe being a little bit forced and cheesy and predictable. Instead, it feels like a precious morsel of hope ready to be savoured by the reader. It is a gentle reminder that we are allowed to want good things to happen, and there is joy and goodness in the world, even in the darkest times. While the language and content in this novel may not be suitable for all young readers, there are so many who will benefit from the happy ending of Eira and Soren, and who will carry their happiness with them as they face the world.

Lindsey Baird, a high school English teacher on Treaty 7 Territory in Southern Alberta, recently completed her M. Ed in Critical Studies in Education.