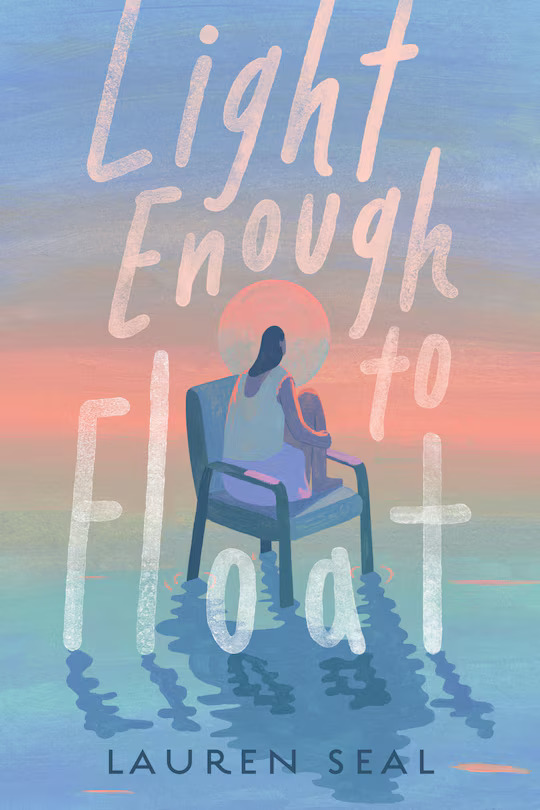

Light Enough to Float

Light Enough to Float

Excerpt

my muscles lock tighter

than the unit’s metal doors.

i refuse to stand.

mom gently pulls at my arm.

evie, come on.

I do not move

the next tug

is rougher

evie, don’t make this harder.

listen to dr. mantell.

what am I, if not

a good girl,

a smart girl,

an abiding girl?

my knees creak

as I stand. I am

a wooden marionette,

other people’s expectations my strings. (Pp. 48-49)

When 14-year-old Evie is admitted to inpatient treatment for anorexia, she is filled with anger and betrayal. She has just been diagnosed, and now she is locked in, faced with calorie loading, therapy sessions and her own inability to be the “good girl” she has always strived to be.

At first, Evie is surly and uncommunicative, her seething inner dialogue hidden behind terse obedience. Evie feels abandoned by her mother who delivered her and then left her in the treatment centre against her will. She rails inwardly against the rising calorie count and weight gain and is furious with the team that is trying to treat her, but she tamps down her anger as she tries to do what others expect of her. Instead of expressing her feelings, she scratches obsessively at her scalp.

Gradually, Evie responds to sensitive teachers, her counseling therapist, and the camaraderie of some of the other patients, and she begins to unpeel the layers of obsession and self-hatred that feed her eating disorder. Over four months of treatment, she eventually traces a path towards healing and self-acceptance.

In Light Enough to Float, author Lauren Seal infuses the story with intensity. Based on her own experience with residential treatment for anorexia and obsessive behaviour, Seal outlines the daily routine of inpatient care as well as the sense of panic and anxiety at the prospect of “recovery”. The verse novel format creates a parade of intense moments, using poetry to illuminate the concentrated emotions of the main character. Evie’s inner voice – sarcastic, yearning, confused – surfaces through the spare yet poetic language. At first, Evie says little to her counsellor, her fellow patients, or her teachers, but inside she fumes. As she gradually learns to express and accept herself, her inner voice becomes kinder, both to herself and others. Eventually food becomes not an enemy but fuel to live a full life.

The novel provides a window into the psychology behind eating disorders and obsessive behaviours that hijack Evie’s thinking. Food for Evie is an enemy, her need to disappear reinforced by internet images. “diet and exercise posts/became the one thing/I happily ate up,” (p. 85) she says, describing the onset of the disorder as her body matured at puberty. She admires the gaunt bodies of other inmates, and, as the doctor increases her calorie intake, she is horrified at her weight gain. Her overwhelming anxiety is eased by obsessively picking at her scalp until bleeding welts appear, but eventually her counsellor redirects her by giving her wax crayons to pick at instead.

Evie’s relationship with her family members transforms through the course of her treatment. When she is admitted, the only uncomplicated relationship she has is with Harlow, her dog. By the time of her discharge, she no longer sees her sister as perfect, trying to upstage her, but as a sister who wants her sibling back. Her image of her mother changes from seeing her as manipulative and judging to a flawed human being, doing her best to save her daughter. Before she can accept others, however, Evie has to learn to accept herself, to allow herself to exist in the world, rather than trying to disappear. Helped by her team and her family, she leaves the hospital “sandwiched/between dread and hope”, and moves toward full recovery: “I stretch out my arms, my legs,/take up the space my body needs,/and float.” (p. 343).

Seal’s own experience lends authenticity to the narrative, and, in both the introduction and the afterword, she speaks directly to those who suffer from disordered eating. When she was going through the experience, she writes, she needed a book like the one she has written. Those suffering from eating disorders who read this accessible and disturbing verse novel will feel less alone, knowing that Seal has overcome a painful and life-threatening condition and thrived in her life on the other side.

A poignant book on a painful subject, Light Enough to Float is a story of hope and personal triumph that will resonate with many young readers.

Wendy Phillips is a former teacher-librarian. She is the author of the Governor General's Literary Award-winning YA verse novel, Fishtailing and the White Pine Award nominated novel, Baggage.