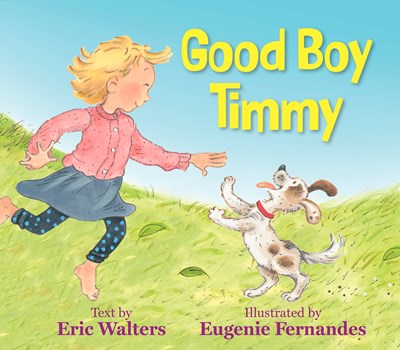

Good Boy Timmy

Good Boy Timmy

“Timmy is such a good boy,” said the little girl.

“He is,” her father agreed. “And really, I think he’s too old to act badly.”

...

I am a good boy…wait…did he say I’m too old?

...

Even though

I am the relative of wild wolves,

the cousin of cunning coyotes,

the descendant of daring dingoes, [……] I know how much she loves that sweater.

I’m not too old to be bad.

But I choose to be good.

Good boy, Timmy.

Good Boy Timmy has a rather uncommon message wrapped in a deceptively conventional package. This review needs a little clarification up front regarding those words, uncommon and conventional, because they have some shades of meaning which aren’t intended but may, nevertheless, be assumed by the reader, colouring their reception of the review: uncommon may be interpreted as extraordinary or odd, and the term conventional, used in a review these days, practically means dull and unoriginal. I mean to use the two terms in the most cut and dried, neutral way: uncommon simply to mean that I do not recall having encountered it in any picture book for this age group I have read so far, and conventional to mean typical and standard. If I am not overthinking the book, this conventional look is a deliberate effect created to maximize the message.

The setting is a nice little probably suburban generic somewhere. We’ve all seen this picture book neighborhood: the little house with its neat front lawn and a little plant in the curtained window, sidewalk with children on swing and skateboard; the little park with its round fountain and wooden bench (the person sitting is reading a magazine or large book, no smartphones or gaming devices here), the pink kite flying, the picnic blanket gaily checkered red and white. Of course, there’s an apple on the blanket, and lunch is a square sandwich with lettuce peeking out the side. People are dressed in blouses with ruffled collars and long skirts with pantyhose, or slacks and button downs that are tucked in. There are sweater vests and cardigans. I am not disparaging the art, it’s an attractive example of a particular kind of setting. It is a nostalgic, safe, timeless world that we have seen before, somewhere. There’s a kind of benevolent haze over everything as if nothing bad can ever happen here.

The story is safe, too, and I bet you’ve read it before: Our dog Timmy is left at home alone, with his owners’ faith in his good behavior. He is tempted to misbehave and dreams of both running with his wild relatives and tearing up the house but resists because he loves his family, and the returning owners reaffirm that he is a “good boy”.

The workmanship on this book is excellent: it is skillfully constructed, and all the elements are, themselves, well-made. The writing is clear and leaves a lot of room for the illustrations to speak, by making deliberate gaps in the dialogue which can’t be understood unless you take the pictures into account. For example, the girl might say “that’s not a toy”, and we will have to look to the illustrations to see that Timmy is running with the girl’s sweater in his mouth – simultaneously setting up the main mischief desire in the story (to wreck the sweater) without ever stating it outright. Timmy’s thoughts to himself are in the first person and are differentiated from the rest of the story which is in a bland third person. The illustrations do their part by having commentary on the text, such as Timmy’s narrowing his eyes and putting back his ears in the picture where the girl and her father are talking about what a good boy Timmy is. This is after the “not a toy” scene – Timmy wants to play with the sweater, and doesn’t appreciate being told he’s too old to be bad.

There are some classic picturebook fun elements like a recurring squirrel, a cactus that appears in real life and in the dream, or having the curve of the pink polka dot curtain mimic the lines of the hanging pink sweater with round white buttons. The style looks like pen and marker, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was drawn first, scanned, and then manipulated digitally after.

All this could have meant a solid, confidently recommended book for storytime, with no surprises at all. A dependable title, but a bit forgettable; that is, if not for the last three lines (seen in the excerpt above and quoted again below) which make the work suddenly interesting:

I’m not too old to be bad.

But I choose to be good.

Good boy, Timmy.

In a picturebook for this age group, we see a lot of basic choices to “be good” modeled: to share, to treat friends well, to brush our teeth, to say thank you and sorry, etc. Mostly I’ve seen it framed as “the character should be good” or “the character is/was good” with the choice shown through the outward behavior and usually rewarded by an authority figure or a happy outcome. So in a picturebook that looks this standard, after having dreamed of being a bad dog and wreaking havoc in the house (and waking gratefully to find it was all a dream), I would expect the text to run something like this:

Oh! It was all a dream. Thank goodness.

“Timmy is such a good boy,” said the little girl.

“He is,” her father agreed. [echoing the text from the beginning and reinforcing that Timmy has now proven how good he really is, thus deserving a reward]

“Good boy, Timmy!” [reward for good behavior in the form of praise]

Instead, while Timmy is relieved that he didn’t actually misbehave, he indignantly contradicts the girl’s father’s assessment that he is too old for mischief, and the girl’s statement that he is unlike other dogs and innately well-behaved: the dream sequence demonstrates that he is much like other dogs, wild and domesticated, and that he still has capacity for mischief on the domestic scale. Following that, he asserts that it is his own choice to be good (because he loves his family) and gives himself praise and recognition as a good boy for this choice, not for the outward behavior. Set up the conventional way (with my humdrum imagined ending), the story is a hypothesis-experiment-proof sequence where Timmy is called a good boy and then must prove that he is one. The little girl and her father are the ones who can validate Timmy, and their approval is what it is worth being good for. With the actual ending, the story is about Timmy being told what he is, interrogating the claim, and coming to his own conclusion. The little girl and her father are not as important as Timmy in this matter, and he literally has the last word. Personal agency is not an uncommon theme in children’s books, but I don’t think I’ve seen it done this way before, and I really don’t think I’ve seen the words “choose to” used in works for this age group. It’s a wonderful example of good picturebook writing (not just any writing–it would not work without the pictures, you see!)

Saeyong Kim is a librarian who lives and works in British Columbia.