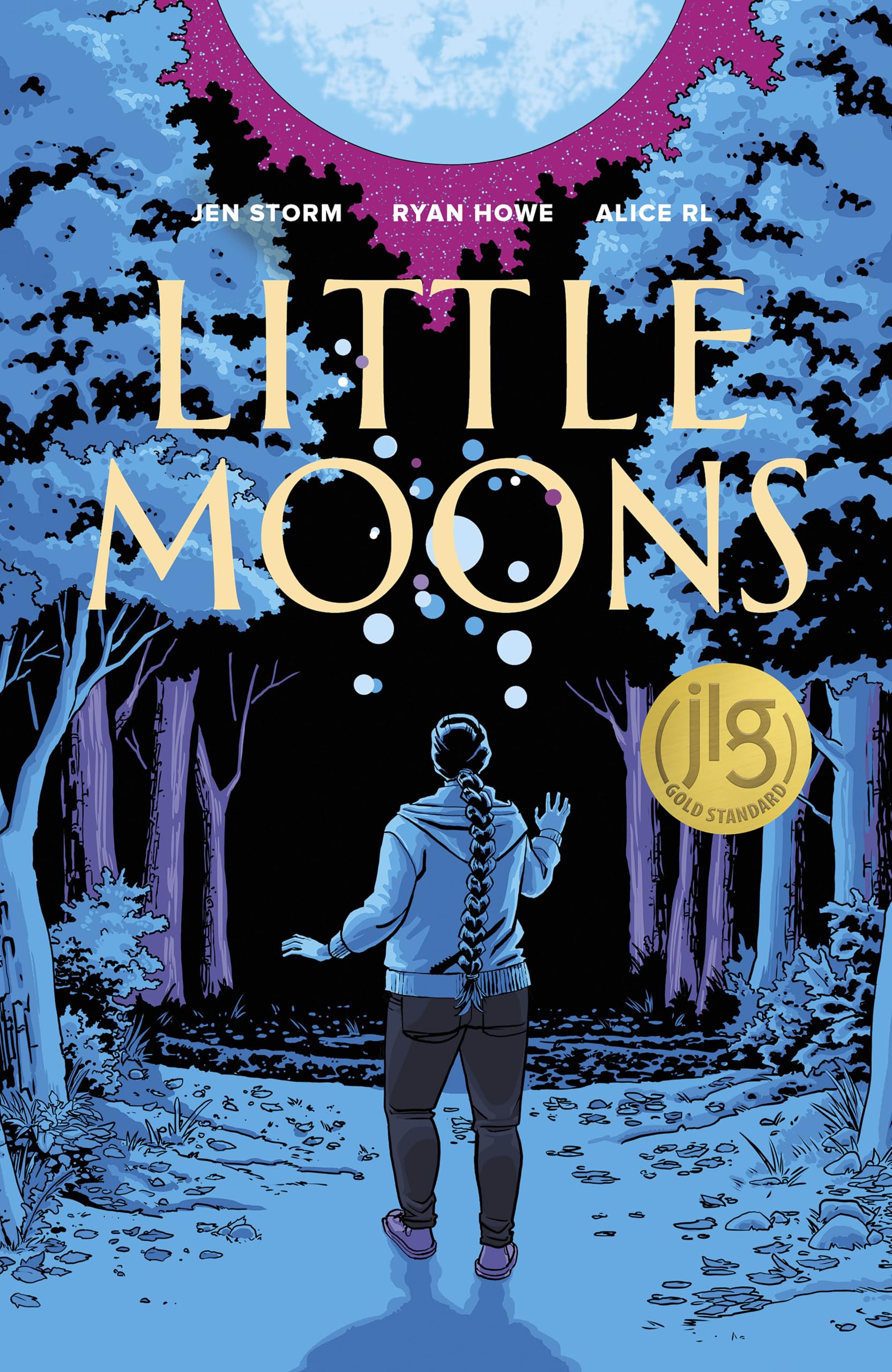

Little Moons

Little Moons

Reanna, 13, lives a typical 13-year-old’s life. She goes to school, hangs out with friends, comes home and spends time on her phone, goes to school and is bored in class, comes home, and so it goes. Family consists of their mother (Andrea), grandmother (Koko), Chelsea (two years older than Reanna), and a little brother, Theo. Home from school, sitting in the kitchen with Theo, Reanna is teased in true older sister fashion by Chelsea. But it’s all gentle, and after the banter, Reanna and her little brother, Theo, head for the room where Chelsea and Andrea are working hard at filling orders for beaded items. Reanna offers to help, and, when told she can choose bead colours, she replies, “No, that’s a baby job. I want to learn to bead for real.” (p. 4) Her first attempt is not great, but Andrea, a master of the art, assures Reanna that she’ll get the hang of it, in time.

All seems fine until evening falls and Chelsea, who has stayed out after school to go shopping with a friend, does not return home. The anguish of Chelsea’s disappearance is conveyed dramatically in several pages of wordless illustrations: first there are phone calls, then text messages, followed by illustrations in which readers see the family searching the area, speaking with the police, and ending with the posting of a “Missing” poster. Months pass and there’s no word, not a clue. Chelsea is now a missing Indigenous woman. One day, Reanna walks into the room where Chelsea and their mom used to work at beading. She takes a square of cloth, some beads, tobacco and cuts some hair from her braid, leaving the little tied bundle at a bus shelter, asking, “Chelsea . . . can you hear me? (p. 13)

The entire family is deep in grief; Anthony, their dad (who lives apart from them) sits crying in the back of his truck, their mom chain smokes and does little else. Koko reminds her daughter that she is an excellent beader and should get back to it, both as a distraction and a source of extra income. But Andrea will hear none of it as beading only reminds her of Chelsea, the time they spent together, and the loss she now feels. Something strange happens when Reanna goes into the bead workroom and picks up a set of beaded earrings: it’s as if there’s a force field, and, when she holds the earrings up to the light in the room, the bulb starts to buzz. The next day, Andrea suddenly decides to get away to the city, forgetting entirely that Reanna is dancing in a powwow. Wearing Chelsea’s regalia, Reanna knows that she will feel a special closeness to her sister.

When Reanna enters Chelsea’s room to gather up her sister’s dance regalia, Koko follows her, encouraging her to participate in this very special event. Koko offers advice: “life is a lot like a river. You can’t argue with a river – it is going to flow. You can dam it up, deflect it, float away on it, fight against the current of it, but you can’t argue with it.” (p. 18) What does it mean? All that Koko tells her is that Reanna will find out. Koko and Theo head off for bed, and Reanna lays out the regalia on her bed before she packs it away. Once again, the light bulb buzzes and fizzles.

At the powwow, Reanna dances her heart out, all the while thinking of Chelsea. Little globes of light – like little moons - appear in the illustration depicting her dance. Is Chelsea there with her? Later, she runs into Cindy, the friend with whom Chelsea was supposed to have gone shopping. They have a moment remembering a friend and a sister, and, when Cindy notices a section of regalia that she helped Chelsea bead, she tells Reanna, “She’d be proud of you.” (p. 21) Once back home, Reanna gets a call from her mother, and it’s clear that something has changed in Andrea. Life in the city is fun, she’s met new people, found a teaching job and suggests that maybe the kids and Koko can move, leaving the rez. During the conversation, Reanna’s phone pulls up a memory of good times spent with her sister, and then, a short video of Chelsea’s dancing with joy in her beaded regalia. Reanna is thoroughly annoyed at her mother, asking her, “Who are you? When did you feel that your life here wasn’t enough?” (p. 23) For Andrea, life changed with Chelsea’s disappearance, and she has dreams she wants to fulfill, one being “owning a beemer,” which she will “never get . . . working on the rez.” (p. 23)

To Reanna, it seems as if Andrea has gone off the deep end, but Koko shows surprising patience with the turn her daughter has taken. Three weeks later, Andrea is back, telling of plans to buy a house, teach Indigenous studies, and take the kids with her to the city. Then, the plan changes again; Anthony tells Reanna that she and Theo will move in with him until Andrea settles herself. Perhaps to distract herself from family turmoil, she works at beading. It doesn’t come naturally and it’s frustrating, emblematic of her life.

Finally, the day of the visit to the city arrives. Andrea is as giddy as a teenager, showing off her apartment which has a must-have amenity: a balcony. She’s thrilled with all of it, especially her new boyfriend, Tom, a car salesman who will arrange a test drive of a beemer, very soon. Something odd happens when Reanna shakes Tom’s hand: the overhead light in the ceiling buzzes and pops. A warning? The four of them head off in Tom’s SUV, picking up coffees and donuts at a local outlet. To say that Tom is a jerk is charitable. As they drive back, he offers up racist rants about Indigenous people not paying taxes and enjoying all manner of benefits. “You guys should thank me. That stuff comes out of my paycheque.” Reanna is justifiably annoyed and texts her mother, “RU rly gonna let him get away with that crap?” (p. 34)

Breaking the tension, Reanna pulls out a beading project which she has completed for her mom. It’s a beemer logo. Andrea is touched, but Tom just sees it as a trinket, failing to understand the craft and skill that goes into even such a small project. They go to a beach, and Tom continues his cringe-worthy behaviour, with over-the-top public displays of affection to Andrea and off-colour, sexist remarks about the other bikini-clad women. Even Andrea is embarrassed. The next day, the kids head back home with Anthony. They were not that impressed with the city.

Once back home with their dad, Reanna reads a story to Theo before sleep. Theo’s not really paying attention, because he says that he sees ghosts and one of them is Chelsea. What do the ghosts look like? He says that they look like little moons. Reanna decides to smudge Theo’s room, chasing away the ghosts, bringing calm to their own spirits. She continues to hear Chelsea calling to her, entreating her sister to tell her where she is. Time passes, and Andrea is still excited about her prospects in the city; she phones to tell Reanna that she’s had a teaching job interview and bought new clothes to look professional. As for Tom, he’s not keen on the kids moving into the apartment, and Reanna see this as a rejection of them and their life: “so, the rez isn’t good enough for you, but it’s good enough for us rez kids?” (p. 44)

It’s an intense conversation, and, after it concludes, Reanna cuts off her braid, dons earrings her father bought for her, makes a bundle with tobacco and her hair and then runs off to her former home. The door to the house is locked so she takes the bundle and buries it, begging her sister to tell her what to do. Should she keep trying to connect with her, or let her go? Her dad comes to take her home, and, as they drive back, a big moon is in the sky hat night. Is it a sign?

Perhaps, but not a good one. The next day, Reanna’s dad receives a phone call from the RCMP, with the news that Chelsea’s handbag has been found but not her body. The hard reality of Chelsea’s fate sets in, and, like Reanna, Anthony cuts off his braid, a sign of mourning. He then states that it is time to have the ceremony that will guide Chelsea’s spirit to rest. That night, the sacred fire is built, and just as Reanna and her dad are about to consign their braids to the fire, Andrea arrives. Tobacco is added to the fire, and then the entire family goes to the place where Chelsea’s handbag was found. Reanna buries another little bundle and prays to the Creator, “Please help my sister find her way to peace, help my mother find herself again, help my family heal their hearts. If we cannot have answers, let us have peace.” (p. 56) Little moons appear as she prays.

The sacred fire continues to burn, and the next day, after Andrea has had her hair (and Reanna’s) professionally cut and styled, she adds her braid to the fire. She’s returning to the city to begin her new job and follow her own path. She has broken off with Tom, and, as she drives off, a little moon illuminates the sky. As the fire continues to burn, she tells Chelsea to “follow the fire home now, baby girl.” (p. 60)

In the book’s final page, Jen Storm, the author of Little Moons, states that the story is from personal experience “of a loved one who went missing and was later found dead.” Her experience is both individual and yet emblematic of the many families of MMIWG (Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls) who live with their unresolved loss. In this story, each member of Chelsea’s family grieves differently and manages the situation in his or her own way. The cutting of one’s hair and the ceremony of the sacred fire are mourning traditions from the author’s Ojibwe heritage, but there are other ways of marking death in Indigenous culture.

Another important tradition in this story is the role of beading as an artistic skill. It conveys culture and connection with one’s heritage. Reanna’s desire to become a skilled beader like her mother and sister show the power of that tradition within her family, and, when Andrea gives it up, it shows the enormity of her sense of loss.

This graphic novel is short - 60 pages of text and frames (often wordless), but it is a powerful story of a family’s tragedy. Reanna’s parents have split up, but her father is a deeply responsible man, doing his best with a truly difficult situation. Grieving people often do strange things, and Andrea’s desire to leave rez life for the bright lights of the city life seems thoughtless. With Chelsea gone, life on the rez seems meaningless, and, for a while, Andrea really loses herself. As for Tom, it’s easy to dismiss him as a stereotypical white guy, an ignorant racist who objectifies women. Regrettably, men like him exist. Koko is truly a wise elder, always thoughtful, and patient with her daughter’s shortcomings. Theo was an interesting little guy. Yes, he plays with his cars and toys, immersing himself in cartoons and toy cars, typical preoccupations of a three- or four- year-old, but there’s something unusual about a little boy who sees spirits in the little moons. As for Reanna, she’s a 13-year-old missing a beloved sister, and, at the end of the story, she faces even more loss as Andrea leaves for her new job in the city.

Little Moons is a book about loss, but it is also a book about healing. Although they will probably never know where Chelsea’s body is, the family does find some comfort in their traditions. Death changes any family unit, and never ever knowing how or why that person died adds an additional layer of pain.

This is an easy-to-read graphic novel, with the colourized illustrations carrying the narrative, even when the frames contain no text. The book’s strong female characters suggest that it’s primary audience will be female. Indigenous communities continue to grapple with the issue of MMIWG, and this book offers insight into that experience.

Little Moons is a worthwhile acquisition for school libraries with students in Grades 9-12.

Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 Territory and Homeland of the Métis People.