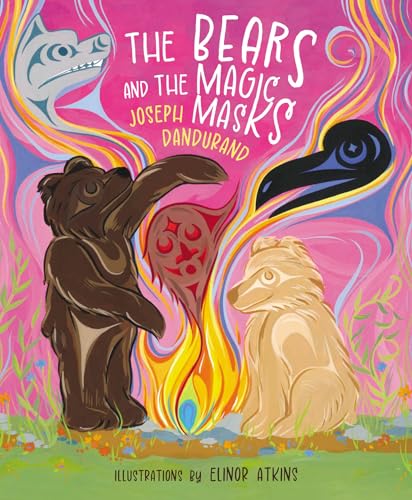

The Bears and the Magic Masks

The Bears and the Magic Masks

What the bears did not know was that these masks were magic masks and if you put them on you would become the animal that was carved into the mask. One night all the young came and danced around the masks and one by one they put the masks on and each bear became that animal. They kept dancing but the songs would change.

With the increased public recognition of indigenous perspectives and mobilization at the grassroots level for greater understanding and reconciliation with indigenous communities around the world, stories provide an important mechanism for the transmission of shared values, beliefs, and worldviews. Historically, indigenous peoples in mainstream literature have often been portrayed by non-indigenous authors, many of whom misrepresent, exoticize, or disavow those communities. However, a growing number of indigenous authors today are representing their own heritage in literature and advocating for the communities from which they originate. Through their stories, these authors affirm their respective communities’ shared histories and experiences as well as convey their value and relevance for understanding life in the contemporary context.

Written by award-winning author Joseph Dandurand and illustrated by Elinor Atkins, The Bears and the Magic Masks is the fourth book in the “Kwantlen Stories Then and Now” series, which includes The Girl Who Loved the Birds, A Magical Sturgeon, and The Sasquatch, the Fire and the Cedar Baskets. In depicting Kwantlen people and their relationship with bears, Dandurand conveys a harmonious and mutually beneficial relationship between people and the natural environment, one that is not characterized by humans’ dominance or subjugation of nature, but rather by a healthy co-existence among the two that is characterized by mutual understanding and respect. With its engaging narrative, age-appropriate language, and vivid, colourful illustrations, the book will readily appeal to young readers. Although younger children may find a few words to be unfamiliar, the illustrations will facilitate their comprehension of the story, and adults can also assist with defining any unfamiliar words as needed.

The book’s opening scene establishes the relationship between the main characters, a relationship that serves as the basis for the remainder of the story. Whereas bears may be regarded in certain works of Western literature as threatening animals that people should avoid, Dandurand’s story portrays an amicable relationship between the Kwantlen people and the bears with whom they have lived alongside for many years. The Kwantlen villagers provide fish from time to time, and, in return, the bears would watch out for them and chase away any coyotes and wolves who tried to steal their food. After their master carver falls into the river and gets rescued by the bears, he decides to express his gratitude by carving some magical animal masks for them, masks which depict an eagle, a raven, a wolf, a coyote, and a sasquatch. When wearing the masks, the bears take on the characteristics of the respective animals and feel compelled to dance. Affirming the strong bond between the Kwantlen and bears, the story concludes by reiterating the centrality of the natural environment and expressing a sense of respect and reverence for it.

The story’s straightforward plot will make it easy for young readers to follow, but it also embodies deeper meaning and significance that can be better appreciated in relation to the contexts that inform it. In particular, it is important to recognize the significance of dancing within the cultural context of indigenous peoples as well as the historical context of government-sanctioned practices that aimed to control and assimilate indigenous communities. Indigenous cultural practices and identities are intertwined with the natural environment. As a means for expressing their shared identities, dances incorporate diverse styles within different indigenous communities, each of which has its own origin story, meanings, and teachings. Land-based knowledge has also shaped the teachings and cultural practices of powwows, including dances. Under colonial law and legislation, indigenous practices and ways of life became outlawed. For example, Canada’s introduction of the Indian Act and its subsequent amendments subjected indigenous communities to increasingly punitive restrictions. After outlawing the potlatch in 1884, this was followed by restrictions on their festivals, ceremonies, and dances in all forms. Residential schools contributed to the destruction of indigenous cultures by forcibly extricating indigenous children from their communities, the effects of which persist to this day.

In this context, the story carries greater significance beyond its plot about animals that dance and become transformed due to the magical masks. The book constitutes an exuberant reclaiming and articulation of the Kwantlen peoples’ heritage with dancing and masks as a focal point. Furthermore, it could be regarded as a metaphor for people who assert their identities in an uninhibited and joyful manner. As an integral part of the narrative, masks embody mythological qualities which align with their cultural and historical significance in indigenous communities. Depending on their purpose and function, masks are created in a variety of styles and forms and may assist with the sharing of stories and knowledge. In Dandurand’s story, they affirm the strong bond between humans and nature. His selection of animals for these masks—eagle, raven, wolf, coyote, and sasquatch—is also intentional as these animals have symbolic significance in indigenous cultures.

Elinor Atkins’ colourful illustrations will draw readers into the story and assist their comprehension by highlighting key moments in the plot. Influenced by Atkins’ cultural roots in the Coastal and Interior Salish culture, her illustrations incorporate traditional design elements that are rendered in a contemporary style. In doing so, she conveys the dynamism and vibrancy of indigenous cultures through her brightly coloured illustrations that evoke movement, particularly during the parts of the plot when the bears have put on the masks and are dancing.

Readers unfamiliar with indigenous cultures can still appreciate this story and its positive message of harmonious co-existence between living beings and nature. In the classroom, teachers could use this book as an easily accessible introduction to indigenous communities and their traditional cultural practices, through which students can be encouraged to think critically about various topics. For example, one possible discussion topic is how the book depicts people’s relationship with nature and how this aligns or deviates from other representations in literature or, more broadly, popular culture. Besides prompting students to consider their relationship with indigenous cultures, the book could also function as a starting point for them to reflect on their own cultural backgrounds and the ways in which particular practices become defined as significant and meaningful. Dandurand’s book would also be a valuable addition to any library that would like to build its collection of indigenous literature for young audiences.

In an interview, Dandurand mentions that he wants to preserve, contribute to, and share the histories and stories of the Kwantlen people. Writing becomes a way for Dandurand to tap into his community’s oral-based heritage and affirm their continued existence and strength. In addition, it allows him to educate readers, particularly about the importance of giving back and respecting the earth: “In all my children’s stories and plays, I use the teaching that we should not take everything from the Earth and that we should always give something back, or else we will have nothing left for future generations.”

Joseph Dandurand is a member of the Kwantlen First Nation which is located on the Fraser River near Vancouver. He received a diploma in Performing Arts from Algonquin College and studied Theatre and Direction at the University of Ottawa. Director of the Kwantlen Cultural Centre, he is the author of several children’s stories and books of poetry, including The East Side of It All which was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize. In 2021, he received the BC Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Literary Excellence.

A member of the Kwantlen First Nation and graduate of Langley Fine Arts School, Elinor Atkins creates work that draws upon the traditional teachings of the Coastal and Interior Salish culture as well as a deep connection to the land and water. She has worked in a variety of mediums such as illustration, painting, printmaking, wood carving, and public art installation. She illustrated The Girl Who Loved the Birds and A Magical Sturgeon, with the latter being longlisted for the 2023 First Nations Communities READ Award.

Huai-Yang Lim has a degree in Library and Information Studies. He enjoys reading, reviewing, and writing children’s literature in his spare time.