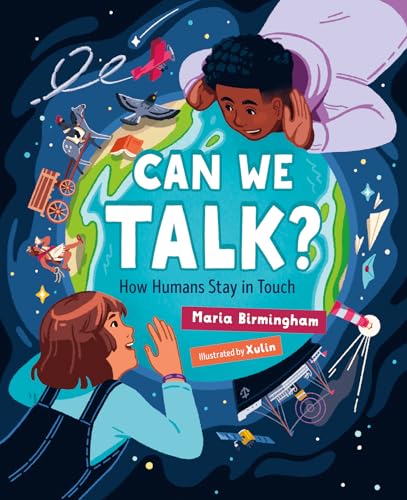

Can We Talk? How Humans Stay in Touch

Can We Talk? How Humans Stay in Touch

While we can’t say for sure when humans began to communicate with speech, it’s interesting to think about why we began to use it. Why did we need to go beyond communicating through gestures? There are several theories about this. Some experts think that as humans began to use tools about 2.6 million years ago, their hands were busy, and this made communicating through gestures too difficult, so they gradually began to speak. Another theory is that humans needed to stay in touch when they couldn’t see each other. They might have been too far apart to see someone’s gesturing or perhaps the darkness of night made it impossible to communicate using their hands. And in order to survive in the harsh world, people needed to share information about things like food, water, and shelter. Given that, experts theorize, humans had to find another way to “talk,” and using their voices became a way to do just that.

In Can We Talk? How Humans Stay in Touch, part of the “Orca Timeline” series for middle-grade readers, author Maria Birmingham looks at the different ways humans use to communicate, both now and through history, from gestures to emojis.

The first chapter looks at the development of human communication and human speech as the two didn’t happen at the same time. It is likely that prehistoric humans used gestures, not speech, to communicate. What type of speech first emerged is discussed although these are only theories. The uniqueness of each human voice and why this is so finishes the chapter.

The next chapter examines human languages. We don’t know what the first language was, or if all current languages had the same origin far back in history. Next to be discussed is how languages spread and why we have so many languages. The book then moves on to languages that have disappeared or are endangered, like many Indigenous languages, and why this has happened. The chapter concludes with the impact of technology on both new languages and endangered languages.

Can We Talk? next looks at non-verbal communication through history, from smoke signals and lighthouses to music and writing. Some myths about some of these communication methods are dispelled, such as the myth of the prevalence of smoke signals as a form of communication for North American Indigenous peoples. Writing is discussed, starting with cuneiform and hieroglyphics, then moving on to alphabets and emojis. Birmingham also covers how written and non-written messages have been sent through history, from early couriers to the postal system.

The last two chapters cover technology and the changes that technology has brought to communication. As with the other chapters, this one starts with early technology, such as the printing press and Morse code, moves on to the telephone and television, then computers and the future of communication.

Each chapter’s being broken down into smaller sections makes for easy reading. There are multiple “Tell Me More” boxes that provide additional information on topics that aren’t covered in the main text, such as Braille, the way Alexander Graham Bell wanted to answer the telephone, and why we get a squeaky voice from helium. Other topics are given a “Talk About It” page, with additional information on topics like steganography (hiding messages within or on top of ordinary things that are not secret), or unusual languages like yodelling or textese. These are great ways to highlight additional information for readers. There is a glossary for terms that readers might not know and a page for additional resources, both print and online.

The book is wonderfully illustrated by Xulin. From smoke signals to printing presses to masks amplifying actors’ voices, Xulin’s lively and colourful illustrations bring the concepts to life visually.

Can We Talk? How Humans Stay in Touch provides an excellent overview of human communication and its history. Everyone can learn something new about human communication from this book and be inspired to find out more.

Daphne Hamilton-Nagorsen is a graduate of the School of Library, Archival and Information Studies at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia.