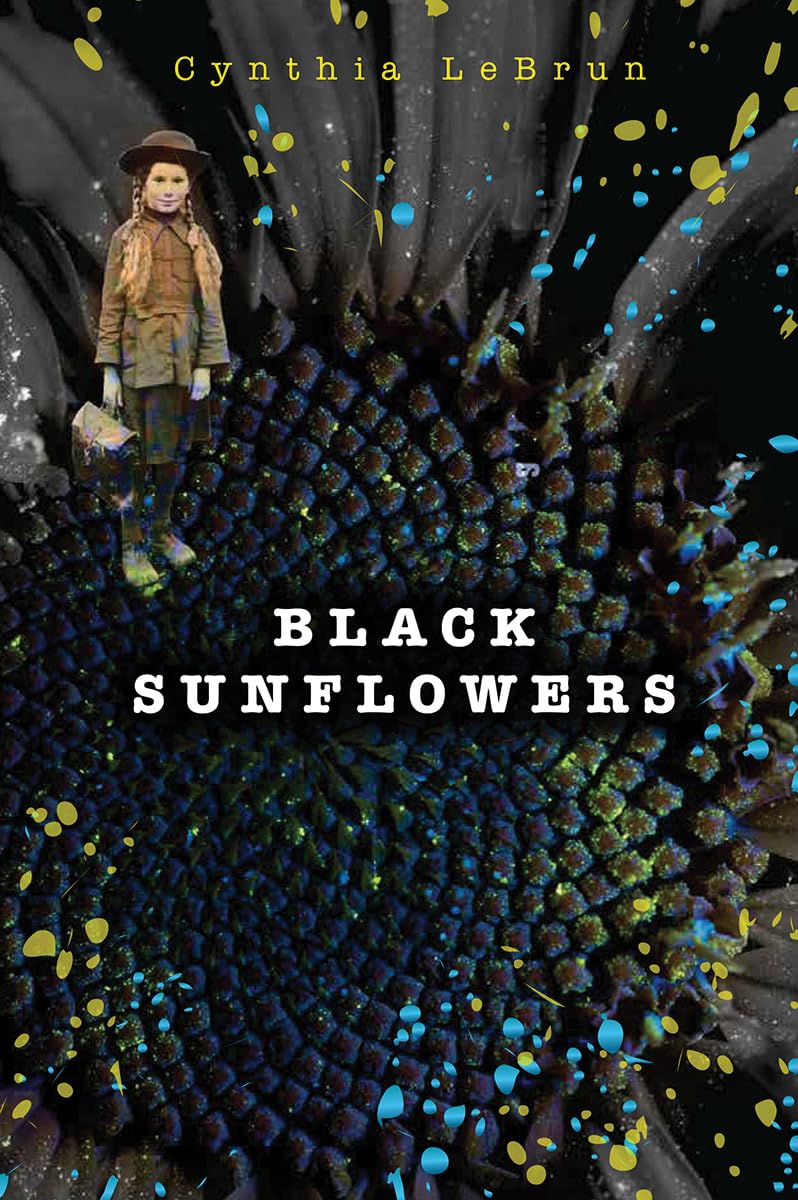

Black Sunflowers

Black Sunflowers

As Veronika skipped down the road and her home came into view, she felt a deep happiness. So strong and beautiful her home was with its whitewashed stone walls and tile roof. Wisteria vines covered the front wall of the house; when it was in bloom, the wall was a mass of purple flowers. Against the wall of wisteria, was a stone bench. Beside the house was an enormous vegetable garden, and directly behind was an orchard of cherry, plum, pear, apple, and walnut trees. Beyond that were their grain fields, where Tata grew mostly buckwheat. (Pp. 13-14)

Black Sunflowers begins in November, 1929, when Stalin's policy of collectivization is well underway. The Soviet state eliminated ownership of the family-owned farms, turning them into “collectives”, large agricultural estates intended to be more efficient and productive than the small, unmechanized farms worked by peasants. Told through the dual perspectives of young Veronika Osiecki and her father, Jan (Janek), the story concludes in 1942, with the German army’s occupation of Ukraine. Veronika’s immediate and extended family live and farm near Kuzmin, a village in Khmelnytskyi, a western Ukrainian province bordering on the Polish frontier. For centuries prior to World War II, national borders were fluid, and, at times prior to the Soviet Revolution, portions of Ukraine were sometimes under the rule of Poland, Lithuania or Russia. Veronika’s family are ethnically Polish, and Kuzmin village is unusual for its diversity: Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews live together peacefully. Although antisemitism was rife in Eastern Europe, Janek is tolerant, believing that “there’s good and bad in all people”. (p. 103)

Typical in rural villages of the time, Veronika’s extended family lives close by, and, while there are differences, tensions, and secrets, family is everything. Her grandmother, Babcia Antosia, is cantankerous, dismissive of her daughters-in-law and grandchildren, but everyone puts up with her, although not without complaint. However, Babcia is justified in her complaints about the continuing round of taxation which the farmers are made to pay and the unrealistic grain production quotas demanded by the Soviet government. At the beginning of the story, these small family farms are self-sufficient although the work is hard, and unmechanized. The produce of the garden and orchard is preserved and stored in the family’s root cellar, keeping them well-provided.

However, days before Christmas, a special meeting has been called, and, at the meeting, Comrade Nicolai Zykov, sent from Moscow to serve as the director of the village collective, announces the new directives regarding the disposition of the grain that has been harvested. His announcement is full of lies, claiming that there is a shortage of grain, and that farmers have been hoarding it so that they can sell it on the open market for a better price. As a result, the Soviet government has established quotas to ensure that it obtains the grain it believes it is due. The quotas are completely unrealistic; some grain must be kept for food, for feeding the farm animals, and for sowing the next year’s crop. Christmas Eve is celebrated, but the next day, the warmth of the season is ruined by the sudden and violent arrival of soldiers who raid the family’s cellar where grain has been stored, taking ten of the fifteen sacks.

This raid is the start of life in a state of constant terror and anxiety. Soldiers and government agents conduct house-to-house searches, inventorying the villagers’ simple and home-made household goods, to determine whether they are kulaks, the derisive term for those farmers who are better-off and/or opposed to the collectivization. The soldiers also wage Stalin’s war against religion. They toss Helena’s prayer book into the stove and smash a statue of Mary, the mother of Jesus, a family keepsake and object of respect. Janek, seeing no other option if he is to stay alive, with a simple “X”, he signs over his land to the government. Helena, Veronika’s mother, is horrified at the results of the torture inflicted on her husband’s hand, slammed repeatedly in a door jamb. He reassures her, “Don’t cry. At least we are not registered as kulaks. We still have our house, our garden, and our orchard.” (p. 68)

Before she starts school, Veronika still enjoys the pleasures of playing with her friend, Kazia. The two take delight in mild mischief, like pulling vegetables from Babcia’s garden. But both girls notice that, since working on the collective, their parents are tired and stressed, conversations are guarded, and there is much happening that they don’t understand. When she turns seven, Veronika is sent to school, but, because Kazia is not old enough to join her, Veronika wants to wait until the next year. Her parents, both illiterate, have hopes and dreams that Veronika’s life will be better than theirs and stand their ground. However, school starts terrifying. “Russian was the only language allowed, and she didn’t know any Russian. Anyone who spoke Polish or Ukrainian, even on the playground, would be punished.” (p. 104) School was an important mean of political indoctrination, and the children are taught that Stalin is a hero who loves the people. One day, on her return from school, Veronika starts to sing one of the many patriotic songs they are taught. Her parents are upset and angry that their daughter is being turned into a little Communist. Jan tells his daughter that she must keep silent about her parents’ political opinions because he will be taken by the authorities, never to be seen again. From then on, Veronika is fearful for her parents, mistrustful of former friends, and hates singing songs praising Stalin.

As the years go by, the villagers live in continual fear, distrust, and anxiety. A casual comment is interpreted as criticism, and criticism leads to the rounding up of anyone suspected of disloyalty to the Soviet regime. Fear for basic survival dominates lives as the crops resulting from collectivization are less than expected, poorly stored, or go unharvested. The government’s grain quotas because impossible to meet, and “harvesting of grain from family gardens was now forbidden under penalty of being shot.” (p. 157) Over time, other food stuffs – potatoes, dried fruits, nuts – became scarce, as well. The Holodomor, death by famine, had begun.

Desperately hungry people – children and adults - roam the countryside, sometimes turning up at the Osiecki’s doorstep. The family offers what they can, but their own food supplies are running low. Family treasures – jewellery, coins – are exchanged for bread and other foods at the Torgsin, a store created by the government to extract the last of the peasants’ diminishing resources. Travel to other areas becomes nearly impossible as special permits are needed. Janek bribes an official, obtains a travel permit, and heads north to a town where he and his brother Oryst hope to sell knives. But as the train pulls into Proskurov, he is shocked at the “sight of the walking skeletons who lined the tracks. Arms outstretched, men and women pleaded for help while some held children with wizened faces aloft.” (p. 196). He is moved by pity and overwhelmed by his own helplessness. Worst of all are the bezprizorniki, the homeless street children made feral and dangerous by their hunger. Oryst and Janek head further north, hoping to try their luck elsewhere, but instead encounter empty villages, its inhabitants starved to death on government order. Sometimes, the two men share what little they can with desperate children, but it is hopeless, and, always, they fear for the fate of their own families.

In mid-June of 1933, Janek returns to Kuzmin. But Veronika’s joy disappears when her father recounts the horrors of the dead villages and, especially, the plight of homeless children, hunted down by police, and packed into boxcars left on the rail siding where they died. It’s the stuff of nightmares, but, at school, Veronika continues to sing the praises of Stalin. It’s the price of safety. Back at school, Veronika notices that some of her classmates are missing, but a new group of students has arrived. They are Jewish and are at the school because their school only went to third grade. Veronika has a new seatmate, a red-haired girl named Frania, the daughter of the kindly general store manager who always made sure that he had her favourite candy in stock. The friendship between the two blossoms, and, on her visits to Frania’s home, Veronika is introduced to a world quite different from hers.

The family’s sense of security becomes increasingly tenuous, and, one night, Veronika’s uncles, Vladzio and Feliks, are taken by the secret police for deportation to Siberia as slave labourers. Feliks’ wife, Paulina, writes to the vice-president of the Soviet Union, begging for help. Two months later, she receives a cryptic reply: “after ten years, then you can hear from him.” (p. 295) Soon, she and her children are also taken by the secret police and are sent to labour in Kazakhstan. After hearing of Paulina’s fate, Janek is tortured by the likelihood that he will be arrested and deported and that Helena and Veronika will be become slave labourers. He thinks “the only thing that could save us is if we were liberated from the Soviets.” (p. 305)

By 1936, Veronika is 13, on the edge of adolescence and with all the concerns that come with that age. She is a good student, and her parents have been saving to send her off to college. Her father wants her to be a doctor, but her heart is set on being a teacher, and once she had “earned enough money being a teacher, she would travel to Germany and see all those wonderful places Aunt Agnes saw growing up.” (p. 309) At school, students like her are actively recruited to join Komsomol, the youth wing of the Communist party. Membership is rather exclusive, with perks like special activities, weekly dances, and travel to Moscow to assist with work on the Moscow Metro. It’s enticing, so she and her friends decide to sign up for an introductory hike and cook-out that is upcoming that weekend. When Jan and Helena find out, they are furious, and realize they must tell Veronika of the dirty work done by the Komsomol to various members of the Kuzmin community. Veronika backs out of the hiking event, and, later, when the secret police round up more neighbours without cause, she realizes the reasons for her parents’ concern.

Veronika’s dreams to attend college come true when she receives her exam results, passing at the top of her class. As she gets ready to leave home, she anticipates a future so different from life in Kuzmin: independence, a career, money of her own, and travel. However, it’s September of 1939, and, when she sees the frightened faces of fellow students on the college campus, her enthusiasm dissipates. Germany has invaded Poland and Kuzmin is close to the Polish border. She does obtain her teaching certificate but spends the summer of 1940 at home before starting her first teaching job in a small village not far away. With imminent threat of German invasion, in May of 1941, school closes and Veronika returns home, much to her parents’ relief. While Helena and Veronika are at the farmers’ market, Janek is frantically thinking about how to save his family. Looking around his home, he recalls memories of the 1914 war, wondering “where could they hide? . . . His eyes fell on the flat wooden cover of the root cellar, just beyond the well, a rectangle of weather wood lying flat on the ground, and he knew that he had found the answer . . . . If the fighting came close, in the darkness deep under the earth they would go and hide.” (p. 402)

Ironically, Kuzmin village is attacked, not by the Germans, but by the Soviets. Under Stalin’s orders, it is bombed, along with the village granaries, buildings, and shops so that nothing would be left for the Germans. As tanks appear on the edge of their field, the Osiecki family hides in the root cellar, emerging when discovered by a German soldier who spares them from death, seeing that they are “harmless farmers” (p. 418). The villagers of Kuzmin welcome the soldiers, believing themselves to be liberated from the Soviets. However, the collective farms remain because the Nazis need their agricultural products and now, the Jews of Kuzmin are targeted. Veronika realizes that the Nazis are no different from the Soviets; they hunted kulaks and, now, they will hunt down Frania, her family, and the rest of Kuzmin’s Jewish community.

Because the Nazis had stated that schools would re-open, Veronika hoped that her teaching certificate would be valid and she could resume teaching. She is told that she will have to wait until the war is over, but she is offered the possibility of work in Germany. Recruiters paint a rosy picture, and, when she visits Kazia, Veronika tells her that “we wouldn’t work on a farm. We would work in a factory, and it would be fun, wouldn’t it? Just think of all the clothes we could buy. And on our days off, we could go to the theatre, to dances.” (p. 451) But in May, 1942, she has no choice. Soldiers arrive at her parents’ home, announcing that, by German government order, young people between the ages of 15 and 30 will be sent to work in Germany. Goodbyes are always difficult, and, as she spends her last hour with her parents, “she clearly saw the fragility of her parents and felt a jab of fear.” (p. 470) Her fear is well-founded; in the village square, the parting of children and parents is heartrending. When they arrive at the train station, they see that they will travel in cattle cars, with no food, no water, and a bucket for a toilet. As the train pulls out of the station, Veronika remembers her last sight of her father, lying on the ground, wailing in mourning at the loss of his daughter. The Germany to which she journeys is not the land of her dreams but the place that marks the loss of the deep happiness she once felt at home.

Black Flowers is a novel based on the life story of Cynthia LeBrun’s mother-in-law, Veronika, who grew up during the Holodomor, the Stalin Era, and then German occupation. Over a period of years, LeBrun, listened to Veronika’s vivid accounts of the past, recognizing that the story needed to be recorded and told. That Veronika told her story speaks of courage because so many of her generation did not share those memories. Offering the narratives of both Janek – an adult who has seen the horrors of war before and wants only to provide for and keep his family safe – and of Veronika – who grows from childhood to adolescence, provides the reader with dual perspectives on the same event or situation. Like any adolescent, Veronika chafed at some of her parents’ restrictions and objections. Through Janek’s eyes, readers can see the reason for their desire to protect her.

The book’s historical context is enhanced by maps of Europe, Soviet Occupied Ukraine, and of Khmelnytskyi. A family tree offers a “who’s who” of Veronika’s extended family, some of whom are seen in a series of black and white photos. The photos also depict victims of starvation experienced during the (Holodomor) famine years and of deportees bound for exile as forced labourers. Many chapters of the book began with a quotation from notable works on the history of Ukraine, the Soviet Union, the Holodomor, and World War II, offering a succinct explanation of the chapters that would follow. The “Author’s Note” provides short explanations to items such as “Why was a Polish family living in Ukraine?” LeBrun includes Polish language expressions in the story, and, while their meaning is clear from context, I wish that she had included a pronunciation key for the benefit of readers who have not heard the language. The final pages of the book include a “Bibliography” of references for anyone wishing to learn more about this difficult time in Ukrainian history.

Although the book is accessible reading, it is not easy reading. Family anguish at separation, distress at witnessing unjust suffering, and unprovoked violence at other human beings all evoke powerful emotional response. Veronika’s family live simple lives, sustained by their faith in God, their commitment to family and community, and a belief in the value of the life that they draw from the land. Black Flowers shows how a dictator’s ill-conceived policies destroyed a people’s way of life, and how war changes individual lives, forever. This is a book that deserves acquisition in high school library collections and especially in schools with a significant population of Ukrainian heritage. It tells a story that is fast disappearing as members of Veronika’s generation leaves this world.

Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty 1 Territory and Homeland of the Métis People.